About Trauma-Informed Teaching

Posted on | Updated

Thompson, Phyllis, and Janice Carello, editors. Trauma-Informed Pedagogies: A Guide for Responding to Crisis and Inequality in Higher Education. Palgrave MacMillan, 2022. (Book available at the Emily Carr University library).

Many of us working in post-secondary education have heard the phrase “trauma-informed” in a variety of contexts, from discussions of student support services on campuses to the ways and content we teach. At the core, trauma-informed education recognizes that traumatic experiences impact many people on our campuses and offers tools for supporting students and colleagues impacted by trauma in teaching, learning and in other campus community interactions.

I recently offered a webinar on trauma-aware teaching with BCcampus. I used the phrase “trauma-aware” because I think that most instructors already practice in a trauma-informed way when we design assignments and classroom interactions with care for student differences with attention to students’ unique perspectives and lived experiences. So, a “trauma-aware” approach seems like a bridge to trauma-informed practice that helps us recognize the ways that our teaching decisions impact our students.

Published in 2022, with many perspectives from the uniquely intense era of the Covid-19 pandemic, the book offers a collection of chapters on topics ranging from trauma-informed theory to curriculum design, assessment, teaching approaches, and teaching resources, making this a thorough overview of trauma-informed educational practice. A trauma-informed approach is introduced as a type of professional awareness and a variety of educational approaches that are distinct from social services. The editors summarize that trauma-informed educational practice “recognizes resilience, embodied knowledge, and relationality as central to the process of healing and the practice of teaching and learning” (8). This definition of trauma-informed pedagogy indicates a community-mindedness to our instructional design and educational activities wherein instructors seek self-awareness about their own power and positionality and value the differences, strengths and knowledges held by learners.

In the introductory chapter, editors Thompson and Carello underscore that a trauma-informed response should always focus on the present tense. The authors offer the question, “What is happening to you?” (2) as central to a trauma-informed approach as it establishes the importance of addressing trauma responses in the present no matter if a traumatic event happened in the past. This approach of remaining in the present is bridged to a second question, “what’s right with you” (2) as a means of helping students recognize and develop their strength and resilience.

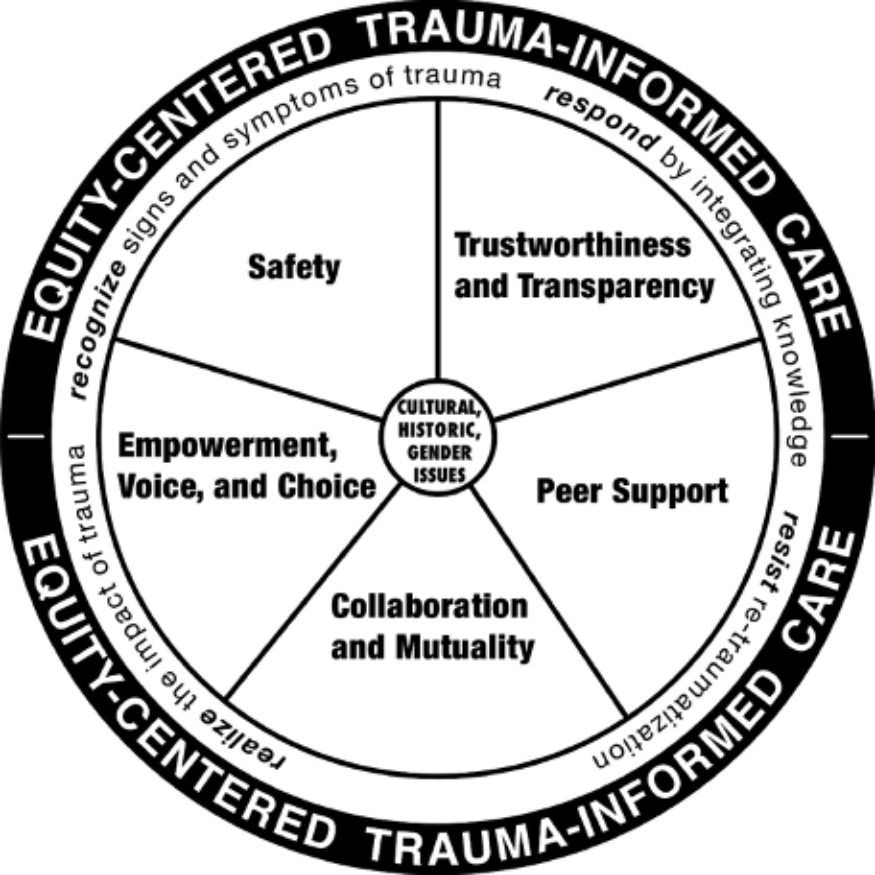

The second chapter by Thompson & Marsh on trauma-informed principles for equity and feminist practice, inserts considerations of race, ethnicity, gender and other identity categories in the centre of trauma-informed care (17) to fully recognize the relationship between identity and experience. With an outer circle always recognizing equity and identity, the diagram below (17) depicts trauma-informed practice as a combination of awareness, educational structure, and specific actions such as prioritizing voice & choice, mutuality (shared decision-making and power), and transparency:

While many chapters offer insight from specific educational disciplines ranging from nursing to social work, most chapters offer fruitful strategies for all educational practices ranging from curriculum, assessment, teaching techniques and decolonizing approaches. Some examples are:

- Chapter 3 reviews the importance of learning journals (like e-portfolios or reflection journals) to support students’ self-awareness and self-regulation in their learning. The author gives the example of a student who came to understand the relationship between their procrastination and trauma through the exercise of the learning journal.

- Chapter 4 underscores the importance of keeping communication lines open throughout the course so that students can revisit class agreements, make alternate assignment arrangements (in timing and format), and receive reminders and prompts from the instructor inside and outside of class time to keep on-track with coursework.

- Chapter 7 emphasizes the importance of “grade-free assessments or other holistic and relationship-based systems of evaluation” (89) as a way of bridging to humanistic, cultural and relational aspects of learning.

- Chapter 8 explores the need for educators to offer students “complex hope” (102) when studying difficult social topics as a means of avoiding silencing optimism that eschews complexity. Complex hope recognizes trauma and violence within historical subjects and designs learning to find pathways to hope through and beyond such challenging subjects towards “material” or even “audacious hope” (102).

- Chapter 17, “What are we centring?: Developing a trauma-informed syllabus,” offers a gamut of educational tools for accessible and trauma-aware course design such as prioritizing students’ chosen names and pronouns, formalizing instructor response times and check-ins, providing clarity in course and grading guidelines, and offering content warnings as a means of letting students know what to expect in the course.

The book ends with an Appendix, a “Trauma-Informed Teaching Toolbox” that has a variety of instructional resources including:

- instructor self-assessment tools,

- sample assignments and class activities,

- reflection and discussion questions, and

- examples of how-to set-up trauma-informed practices such as content warnings.

Overall, this book offers practical and theoretically well-informed approaches to managing and addressing trauma in our teaching and other educational practices.