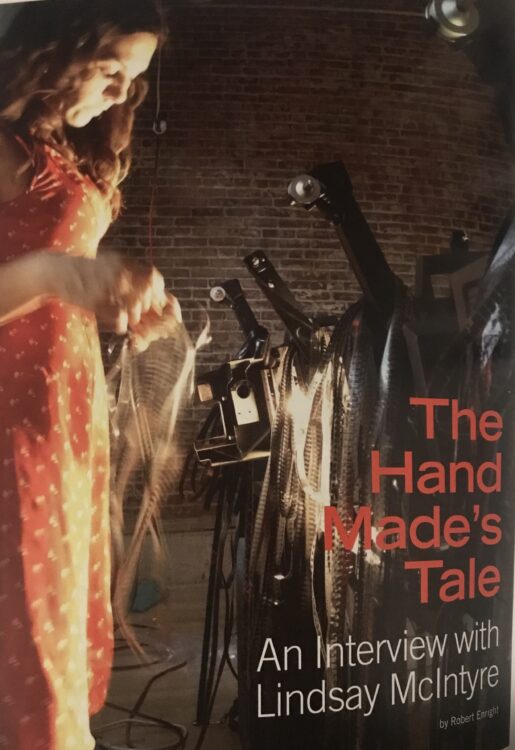

Lindsay McIntyre Named Sundance Institute and Forge Project Fellow

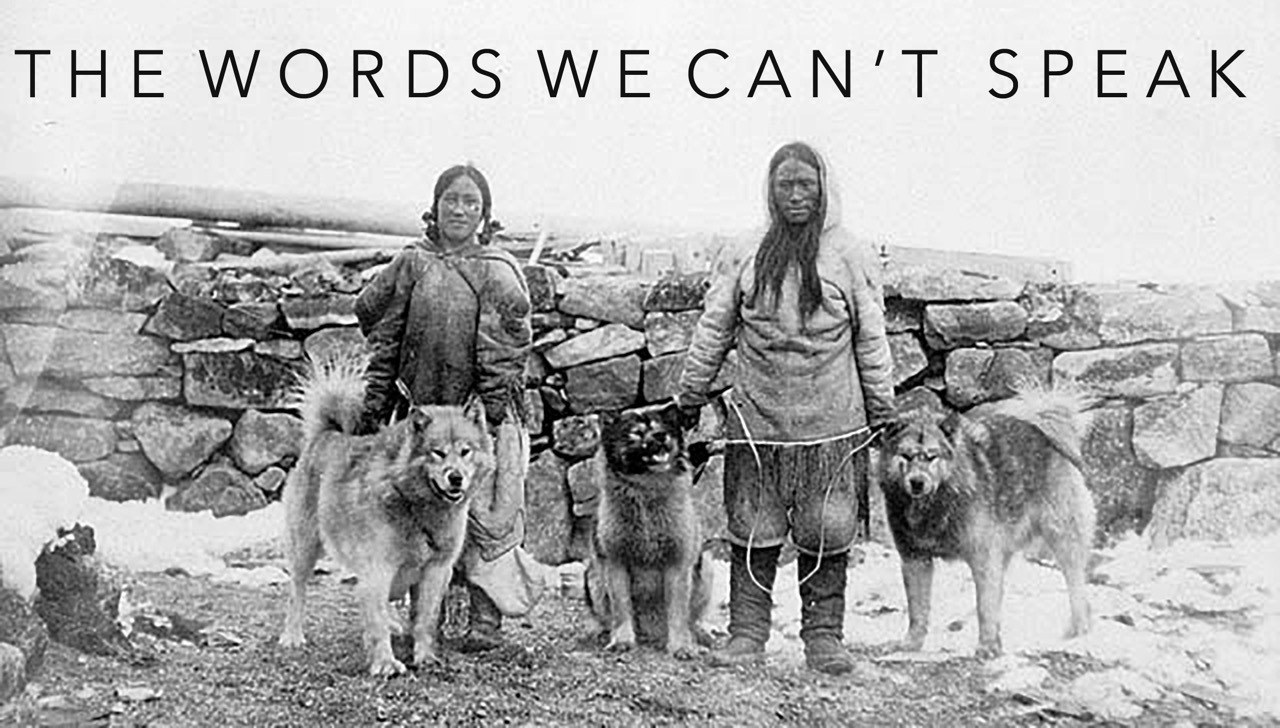

A photo from 1904 depicting Lindsay McIntyre's great-great grandparents in Qatiktalik, NU. (Photo from Library and Archives Canada)

Posted on | Updated

The filmmaker and ECU faculty member brings a pair of personal projects to the renowned fellowship programs in New Mexico and New York.

Artist, filmmaker and Emily Carr University of Art + Design (ECU) faculty member Lindsay McIntyre has been awarded a pair of prestigious fellowships from the Sundance Institute and Forge Project.

Having returned from the initial in-person intensive at the Sundance Institute’s Native Lab, held this year in New Mexico, Lindsay spoke in glowing terms about the experience.

“It’s an incredible group of people,” she says of her peers and the mentorship team at Sundance. “They’re brilliant and very supportive and it’s made a world of difference to have people care so deeply and invest in thinking about what I’m doing, what it could be and how it could happen. It was fantastic being in Santa Fe.”

Lindsay’s focus at Sundance is the script for her upcoming feature film, The Words We Can’t Speak. She’s been working with the story in various forms since 2004, but writing the dramatic feature has been a focus for the past five years.

The narrative is based on the lived experience of Lindsay’s Inuk grandmother in the late 1930s. A version of the story animates Lindsay’s recent, award-winning short, NIGIQTUQ ᓂᒋᖅᑐᖅ (The South Wind), which Lindsay views as a kind of preview of the broader story she hopes to tell.

The Words We Can’t Speak represents Lindsay’s entry into feature-length drama. She notes the time she’s taken with development is a function of the care and integrity with which she insists on treating the story and its telling at every stage.

“To assume you can entertain somebody for two hours or that your story is important enough to tell at that length is not something I’ve ever felt before,” she says. “But this particular story is based on a true story, and in making it, I aim to honour my grandmother, the Inuit community connected to the story and the story itself. It will only be told once and it has to be done right. It’s a story I want everyone to feel in their bones.”

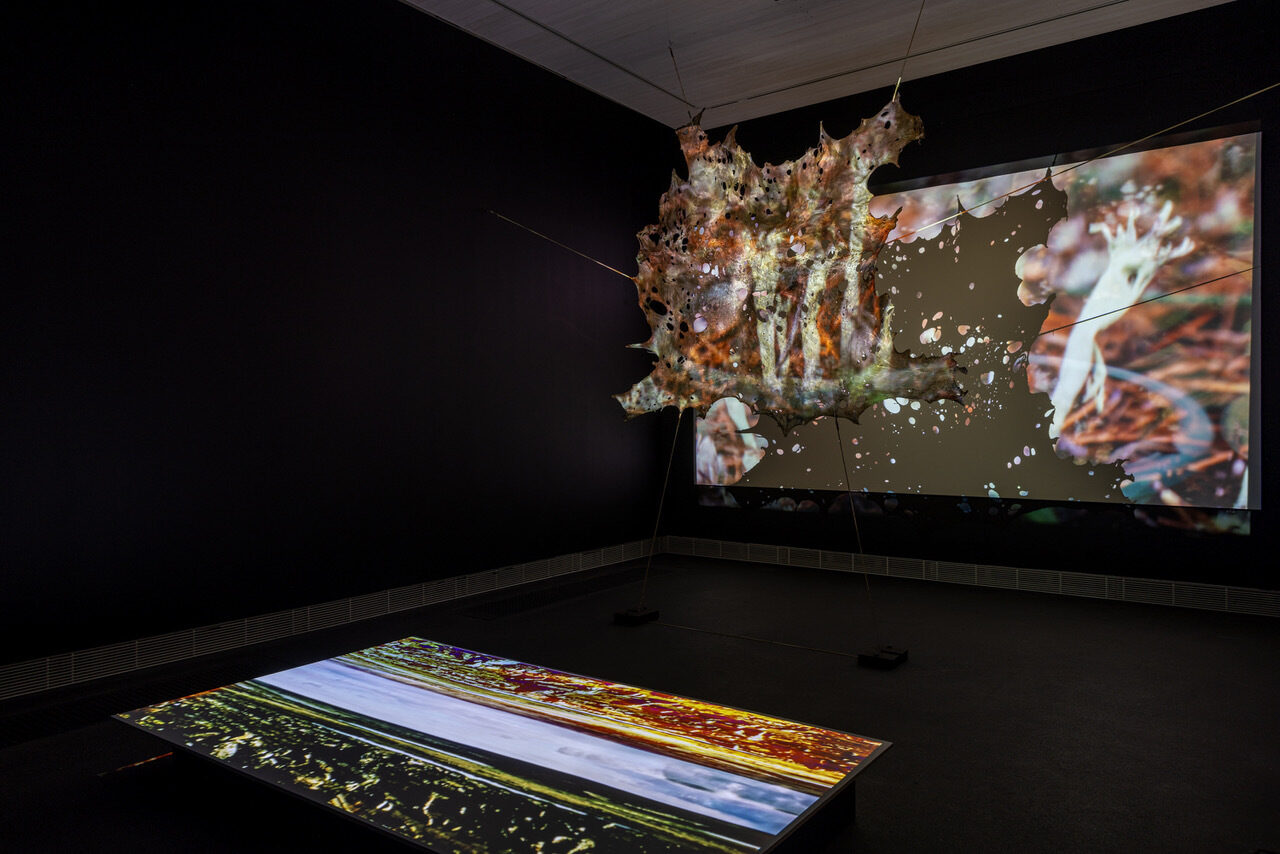

Lindsay used a hand-processed caribou hide as part of an artwork displayed at the Rovaniemi Art Museum in Finland through the spring. (Photo by Tatu Kantomaa, Rovaniemi Art Museum / courtesy Lindsay McIntyre)

Lindsay adds that community consultation and reciprocity have figured into every part of the film’s development and will continue to do so. For instance, shooting on location in Nunavut is a “non-negotiable,” she says. Likewise, it will be important to create mentorship opportunities for Inuit youth throughout pre-production and production and limit hierarchical filming structures.

This model for film production is unusual, Lindsay continues. However, filmmakers such as Zacharias Kunuk, Rhayne Vermette and Sarah Polley are already demonstrating how great films can be made while overturning longstanding paradigms.

“I think it’s important to hold fast to your vision for a project,” she says. “That’s how we make work that is unique, different and important, and that tells important stories.”

Later stages of the Sundance Fellowship will take place at the Sundance Festival in Park City, Utah.

As a Forge Project fellow in residence on the unceded lands of the Moh-He-Con-Nuck in New York, Lindsay aims to continue work on her project Tuktuit, which explores the close and enduring connections between caribou and Inuit. She is currently in the process of re-importing a caribou hide from Finland, where it was on display at the Rovaniemi Art Museum from February through May as part of the ongoing collaborative project Shifting Ground: Mapping Communities and Geographies in the North, led by artist and ECU faculty member Ruth Beer.

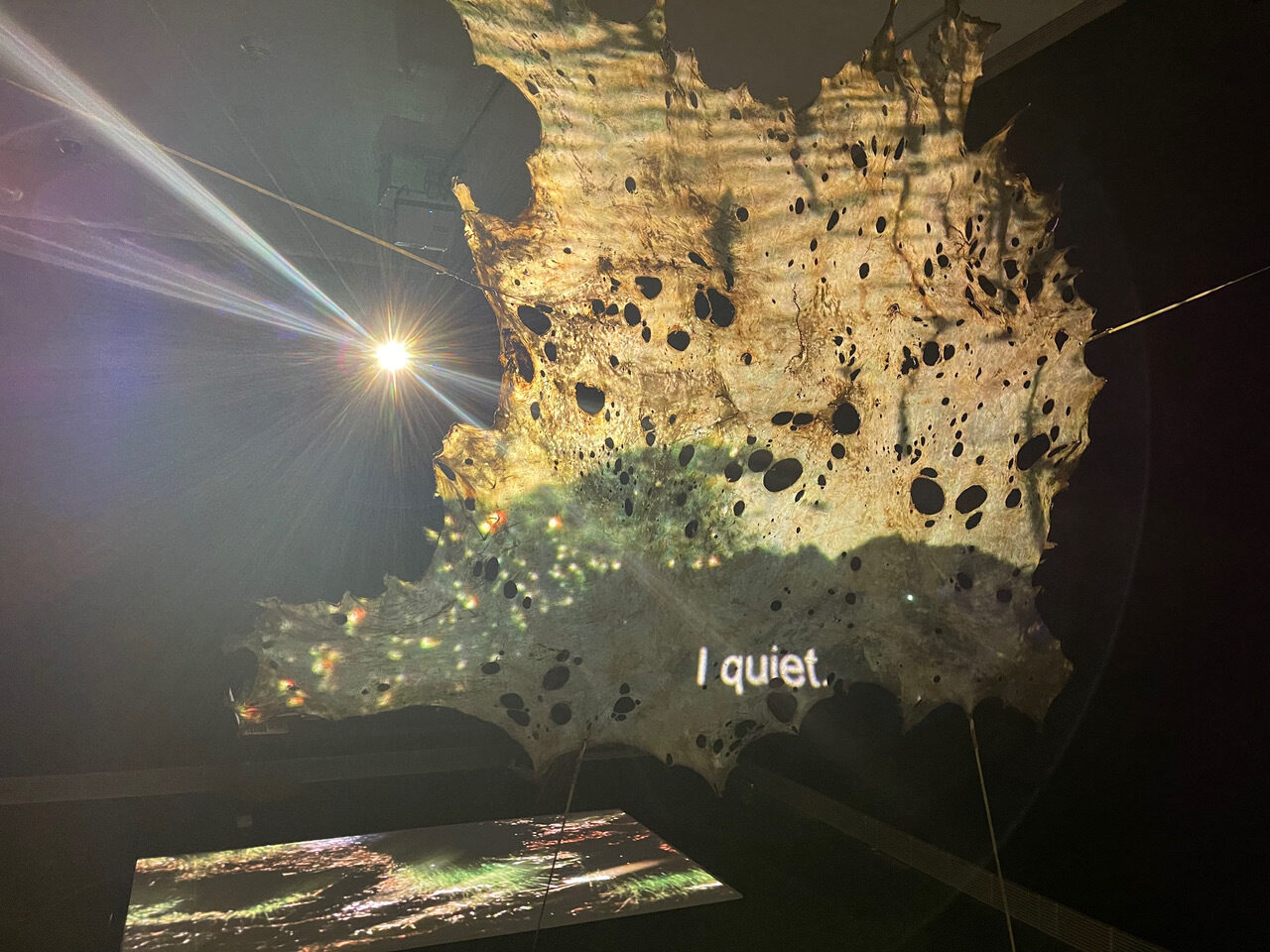

The stretched rawhide served both as an object and as a screen for 16mm footage, some of which was shot on film created by Lindsay using a handmade caribou-gelatin emulsion. The images depict elements of the caribou’s habitat, such as the lichens and mosses upon which they are heavily reliant, as well as the hidework process itself.

This dizzying formal and conceptual interrelationship underwrites the entirety of the Tuktuit project. But like The Words We Can’t Speak, the work is also personal. Lindsay adds this is what makes opportunities like the Sundance and Forge fellowships so meaningful.

The Tuktuit caribou hide bears 893 holes, 25 of which were intentional, the rest resulting from harm due to pests during the caribou’s life, or from mistakes made during processing. “A big part of how I do things is by failing,” Lindsay notes. “I think failure is really important. It’s something that I incorporate into all my classes.” (Photo by / courtesy Lindsay McIntyre)

Both offer a cash prize, public exposure, mentorship and peer support. They also focus on Indigenous leadership, self-determination, place-based research, cultural access, and food, narrative, and visual sovereignty.

Meanwhile, the Forge Project residency is non-project-specific, which Lindsay calls a “revolutionary” format that champions the work a fellow is already doing without tying funding to fixed outcomes.

“It’s unbelievable, overwhelming support. They’re both incredible opportunities and a huge vote of confidence for the projects, for what I’m doing, for the fact that I don’t sleep and work nonstop. It makes it all feel like it’s possibly worthwhile,” she says.

“I never expected to be included amongst the fellows for either of these incredible organizations. The people involved and the care and attention in both of them — it’s a gift. I don’t know how else to describe it.”

Visit Lindsay’s website and follow her on Instagram to learn more about her work.

Visit ECU online to learn more about studying Film + Screen Arts at Emily Carr University.