Kirk Tougas Wants You to Hold That Thought

Filmmaker Kirk Tougas is the recipient of a 2024 honorary degree from Emily Carr University. (Image courtesy Kirk Tougas)

Posted on

The key contributor to West Coast avant-garde filmmaking, founder of The Cinematheque, renowned Canadian documentary cinematographer and recipient of a 2024 Emily Carr Honorary Doctorate reflects on the extraordinary power of art and storytelling.

“Many artists over the years have said, with a certain amount of frustration, they don’t like the term ‘experimental film,’ but we continue to use it primarily because everyone sort of knows what it means,” Kirk Tougas tells me. “So if you say, ‘I make experimental films,’ it sort of makes sense. The problem is that it’s a totally incorrect description of the films.”

Kirk and I have met in a coffee shop near his home in Vancouver’s Commercial Drive neighbourhood to discuss his sterling career as he prepares to accept an Honorary Doctorate from Emily Carr University — one of two 2024 honours bestowed upon distinguished practitioners for significant contributions to the arts.

The esteemed filmmaker has been at the heart of West Coast film culture for more than five decades. As the founding director of The Cinematheque, Kirk established a centre devoted to the art and history of world cinema. He is a key figure in the emergence of avant-garde filmmaking in Vancouver in the 1970s and remains an active and highly regarded practitioner today.

He is perhaps best known as one of Canada’s preeminent documentary cinematographers with a remarkable career of over 250 documentaries. His collaborations with celebrated directors, including Nettie Wild, Linda Ohama, Bonnie Klein, Hugh Brody and Sturla Gunnarsson, produced some of the country’s most acclaimed examples of nonfiction cinema.

“The documentary is, for me, a vital artform — a direct descendant of oral story-telling, drawing images in the sand or on cave walls, trying to understand and survive in this world,” he says.

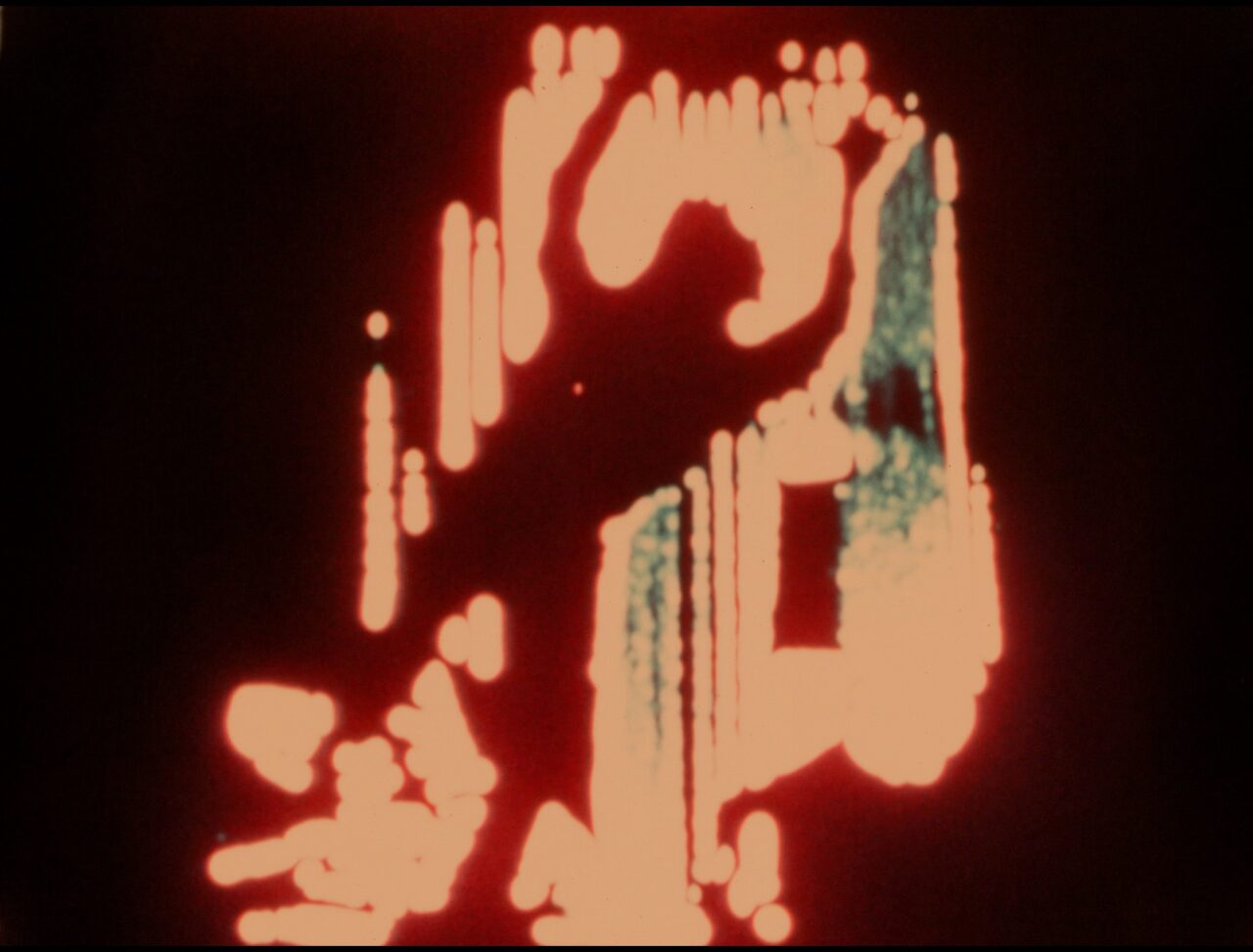

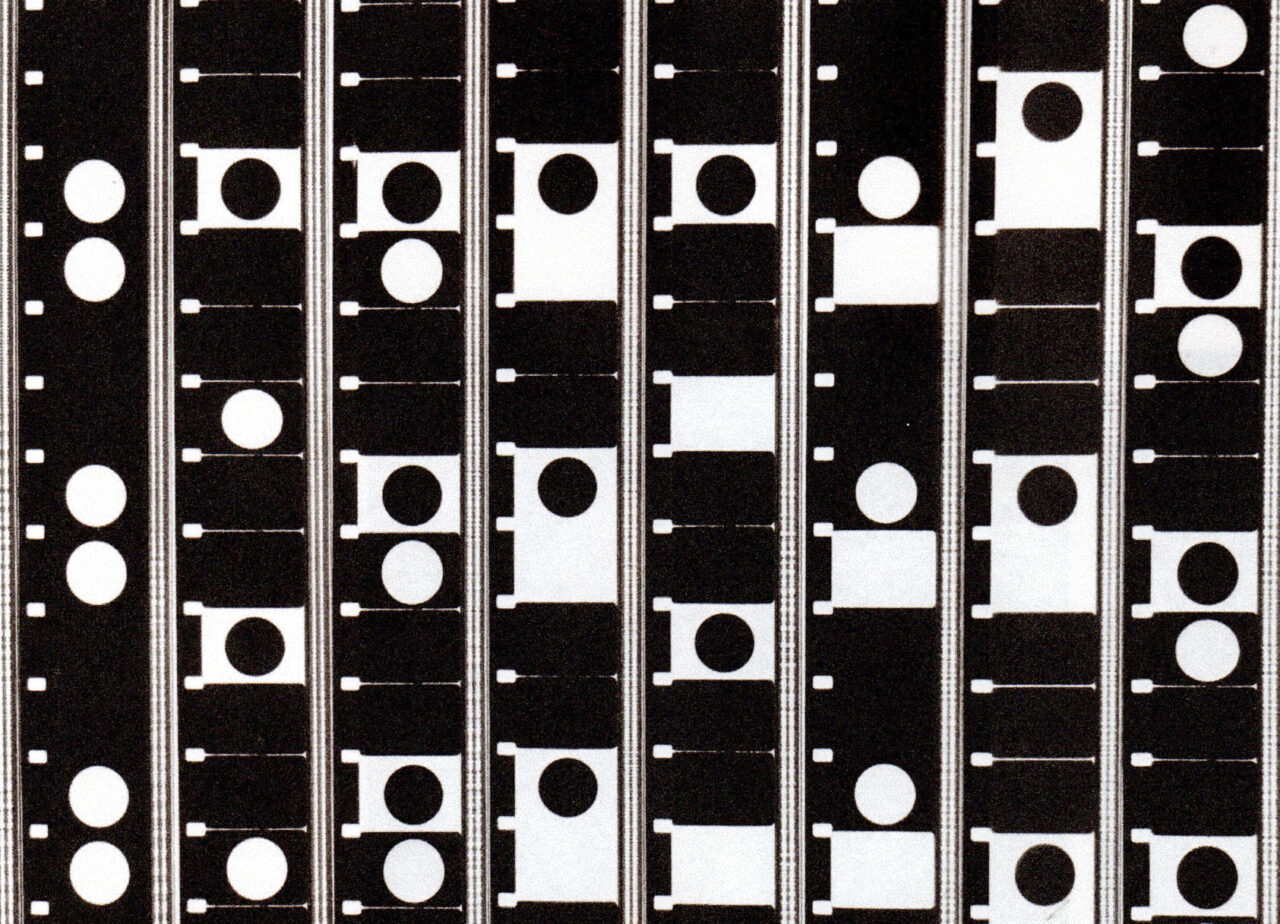

From Kirk Tougas' 1973 films the politics of perception (top) and the framing of perception (bottom). (Images courtesy Kirk Tougas)

But when it comes to “experimental” films, Kirk’s reflection on our understanding of what, exactly, that definition entails is borne out of a decades-long engagement with the form in the broader context of avant-garde art-making in his home city.

“‘Experimental’ films are only experiments insofar as all art is experimentation until it’s finished, or at least released into the world. Then, it’s not an experiment anymore. It’s a completed work. It’s no longer trying something. It is something.”

For Kirk, all art is communication. From its origins in storytelling to painting, sculpture, dance, music or song, each form constitutes a language through which an artist might speak. To frame this enunciation as “experimental” is to frame it as incomplete or even haphazard, undercutting the degree to which its author is committed to shaping and expressing their artistic concerns.

“That’s why I call my work ‘experiential,’” he continues. “I’m creating an experience for the audience.”

For an artist whose films have been described as “structuralist, materialist, conceptual,” the term “experiential” relieves some of the pressure on audiences to imagine there is an intellectual undercurrent they must somehow identify beneath the formal innovations that characterize his heady work. This isn’t to say that such undercurrents don’t exist. They do, and they’re important to him. His work variously meditates on the power of moving images, media deconstruction and the consequences of transitioning from an analog world into a digital one.

From Kirk Tougas' 2018 film Artifact (circa 2006). (Image courtesy Kirk Tougas)

But expressing these preoccupations is the job of the artist, he notes. The audience has a very different job.

“In life, we’re always jockeying between the known and the unknown,” he says. “Art is a fragment of that unknown. For a moment, you’re curious, possibly fascinated by this unknown. Unfortunately, there often follows a rush to judgment; the analytical mind kicks in.” He believes “wonderment” best describes his own response to an artwork. “Leave the interpretation to later.”

This position echoes Kirk’s own development as a lover of cinema. While growing up, he visited other countries on summer break with his parents, both teachers. Having regularly attended Saturday matinees with his grandmother in Vancouver, Kirk was already a budding film devotee. But in Europe, he first encountered an arts community “taking film seriously.”

European critics spoke of “mythology at work” in discussions about American Westerns. Reflecting on Kenji Mizoguchi’s 1953 film Ugetsu Monogatari, they made comparisons with Shakespeare.

From Kirk Tougas' 2018 film Artifact (circa 2006). (Image courtesy Kirk Tougas)

Kirk was enthralled. This art form that had captivated him — which he’d allowed to wash over him in dusky theatres and imbue him with its intoxicating power — was capable of reaching back into history to join hands with humanity’s most ancient storytelling traditions.

“Storytelling is primal,” he says. “In a darkened theatre, you are small in relationship to the large screen. This is a place where we blend into myth and dreams. It has a very fluid, magical kind of rapport.”

This, he adds, “is the place The Cinematheque came from — all the myths and dreams and hallucinations of the entire world.”

Kirk remains committed to creating opportunities for encounters with the unknown. Realizing that avant-garde filmmaking in BC had become nearly invisible, he discussed with VIFF’s Tom Charity the possibility of using their new Studio Theatre as a monthly venue for contemporary film and video artists. Kirk also connected with ECU faculty member Lindsay McIntyre, who suggested graduate student Sidney Gordon (BMA 2022) as curator. Together, Xinema was born.

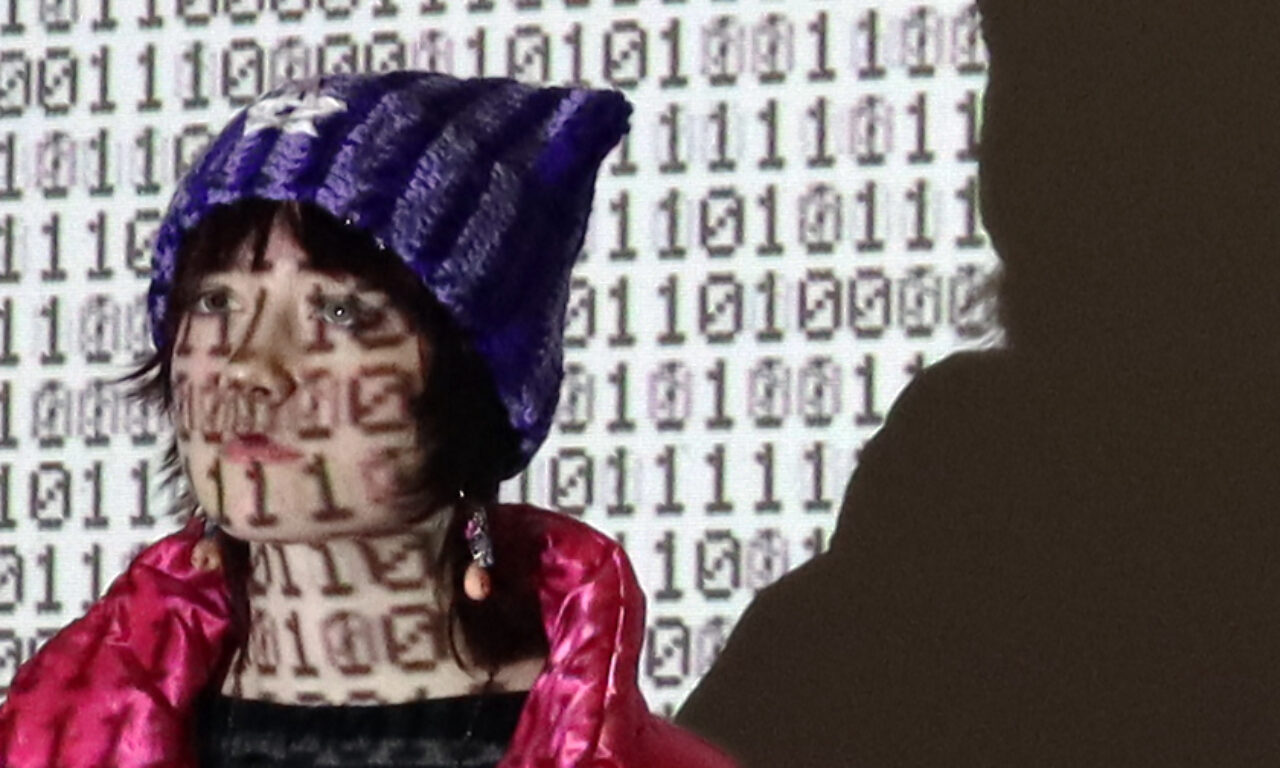

From a new series of works by Kirk Tougas exploring the digitalization of humanity. (Image courtesy Kirk Tougas)

As with Cinematheque in the ’70s, Kirk says Xinema demonstrates how an active artistic community can be a powerful cultural force.

“Culture is a flow. It’s always flowing,” he says. “When you understand there’s something missing in your community, you can act and try to fill that gap. Sidney has the job of bringing forward that which existed but was almost invisible: the West Coast analogue and digital art of today.”

Kirk is also currently at work on a new series exploring the digitalization of humanity. Working with photographs from participants across the globe, he uses binary code as a device to obscure and reframe his crowd-sourced images.

While he feels his themes are urgent—the dangers of humanity’s abandonment of the physical world for a virtual and numeric one, the digital “tattoo” we all carry as our lives are increasingly recorded in all their minutiae—he is careful to note his hope that audiences will first and foremost consider their own personal experience of the work.

Not that he objects to an aesthetic artifact’s historical or discursive possibilities. Instead, those concerns needn’t be the first (or only) vantage point from which the work is viewed.

“Artists will do what they do. A viewer might sense some meaning or feelings, but perception is subjective, based on the totality of one’s experience from the moment of birth to the moment in front of the unknown thing, which we call an artwork,” he says. “Maybe it makes you laugh, maybe it makes you cry. Maybe it’s, ‘Huh?’ or, ‘Wow.’ But you don’t need to try and figure out what it’s about, what it’s saying, what it means. Hold that thought and just interact with the artwork for a moment. The rest can come later.”