In collaboration with nonprofit The Power of Play, Christian Blyt’s second-year design students are producing an interactive object for children in the Gorom Refugee Settlement in South Sudan.

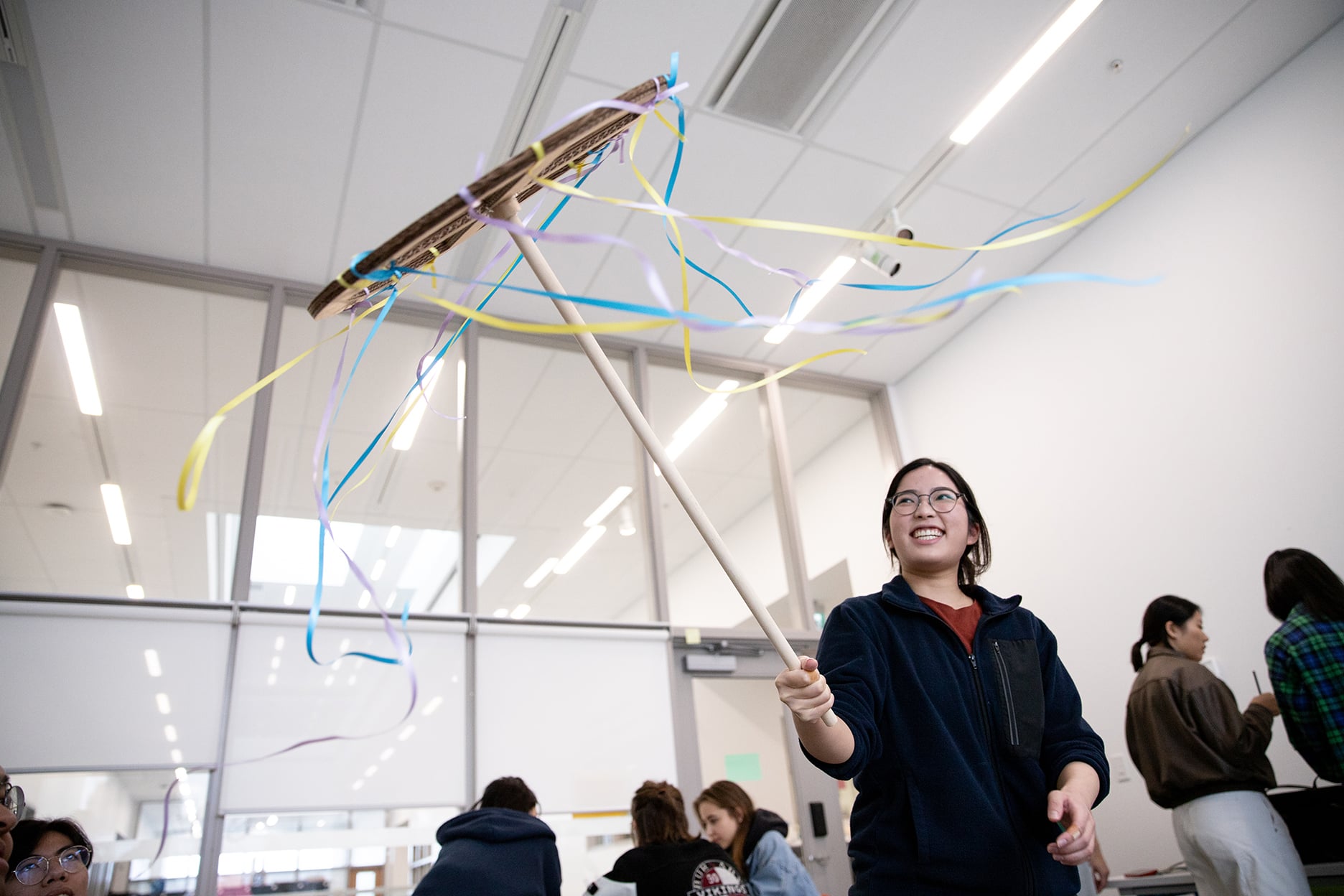

Teams of students in a second-year ECU Industrial Design course are creating interactive objects for children living with trauma.

Led by designer and ECU faculty member Christian Blyt, the class is being conducted in partnership with local nonprofit The Power of Play (TPOP). TPOP’s CEO and founder, Reza Marvasti, says the students have exceeded every expectation.

“It’s amazing seeing the enthusiasm and support for each other,” Reza says. “It’s a sense of true collaboration. The whole idea is to spark collaboration and unity between students and kids around the world. It’s been really inspiring.”

Throughout the semester, students gathered with Reza, Christian and TPOP digital marketing volunteer Ben Khaleghi to exchange project feedback. In March, Christian, Reza and Ben will carefully review each team’s project to ensure durability and manufacturability before being sent to children living in the Gorom Refugee Settlement in South Sudan. More than 1,800 children live in the settlement.

Fusion Studio comprises Industrial Design students Saanvi Bhat, Joey Kim and Tai Vo. Saanvi says working toward a real-world outcome has inspired a new level of passion for her group.

“We have never worked with this much dedication and motivation,” she tells me. “We’re coming back to school after class, staying here for 13 hours, just focusing on finding solutions. The amount of research we’ve done is unreal. This project has unlocked potential we didn’t even know we had.”

TPOP builds sustainable playgrounds across the globe for children in need of space to play. Reza himself grew up in Iran during the Iran-Iraq war. He notes that play is a crucial cognitive and emotional building block. He also knows from personal experience how play can help children process difficult emotions or traumas.

“When kids play to deal with trauma, it’s more about how they’re playing than what they’re playing with,” he says. “It needs to involve simple problem-solving, which a lot of the students recognize. Something too challenging can make kids more frustrated. A lot of what the students proposed involves a challenge and motion that is repetitive and simple – which can be a precursor for imagination. They’re really getting it.”

Sasha Bishop, Luke Higgs and Alex Turnbull form another team in Christian’s class. Since they can’t interact with the children directly, they’re looking at their project as “an exercise in empathy, which all good design should be.” That means “setting aside the designer brain a little bit” to focus on producing a genuine thrill.

Their object resembles a large, modular spinning top. Changing around its colourful parts alters its look and how it spins and dances.

“The first time we got it to spin was a super fun moment that sparked excitement inside of us,” they tell me. “But then you give it to other people and see them get as excited as you were – it’s such a good feeling. It’s like, wow, it’s worth it.”

For Christian, renewed inspiration among his students is not entirely surprising. He says students flourish when offered a real-life application for their design education.

“These are junior designers, and it’s impressive what they’re doing,” he says. “As an educator, to see that kind of passion going into the product — it’s clear they’re not just doing it for marks. They’re doing it because they want to do it.”

Audrey Allanson, Alice (Minsuh) Kim and Sophie Ryznar, collectively known as Jump Studios, suggest it’s more than simple desire, describing the project as “cathartic.” Working together toward a common goal, they’ve discovered a balm for what can feel like an endless refrain of bad news.

“There’s all this horrible stuff around the world and you think, what do I do?” they tell me. “But we realized, no, I can focus on this project. I can change this little thing for this one person.”

Equally powerful was trying to imagine their way into the lives of children living halfway across the globe. In doing so, they’ve uncovered how joy can inform a design process as much as any other constraint.

“Ben told us: remember, these are children just like you were. They have the same inner child in them that you have in you. That’s what we’re trying to bring out,” they continue. “We’ve been pursuing what makes us and other people happy. Whatever sparks the most joy, whatever puts a smile on someone’s face, that’s the thing. Because that same humanity is in all of us.”

Visit ECU online to learn more about studying Industrial Design at Emily Carr.