Taryn Goodwin Is Building a Community of Disabled and Neurodivergent Artists

Posted on | Updated

The disability and social practice artist is creating the change she wants to see at ECU.

For many students, the COVID-19 pandemic has been an obstacle to achieving the university experience they hoped for. But for Taryn Goodwin it presented an opportunity.

The fourth-year Critical + Cultural Practice Major had taken several years off from her degree, having dropped out in 2016, after starting her ECU studies as a second-year transfer student in Fall 2013. While working through physical rehabilitation during her second term at ECU, Taryn knew the pace of education had to be altered.

In 2015, she took a year off through a formal leave of absence to focus on her recovery and to prioritize her mental and emotional health outside of the demands of academia. “I had a couple of exhibitions and worked on a goat farm for a month,” she said, “along with other spontaneous, fun things in continuing to heal and receive support for my mental and physical health. I needed the time. I needed a break. Then I came back for Fall 2016.”

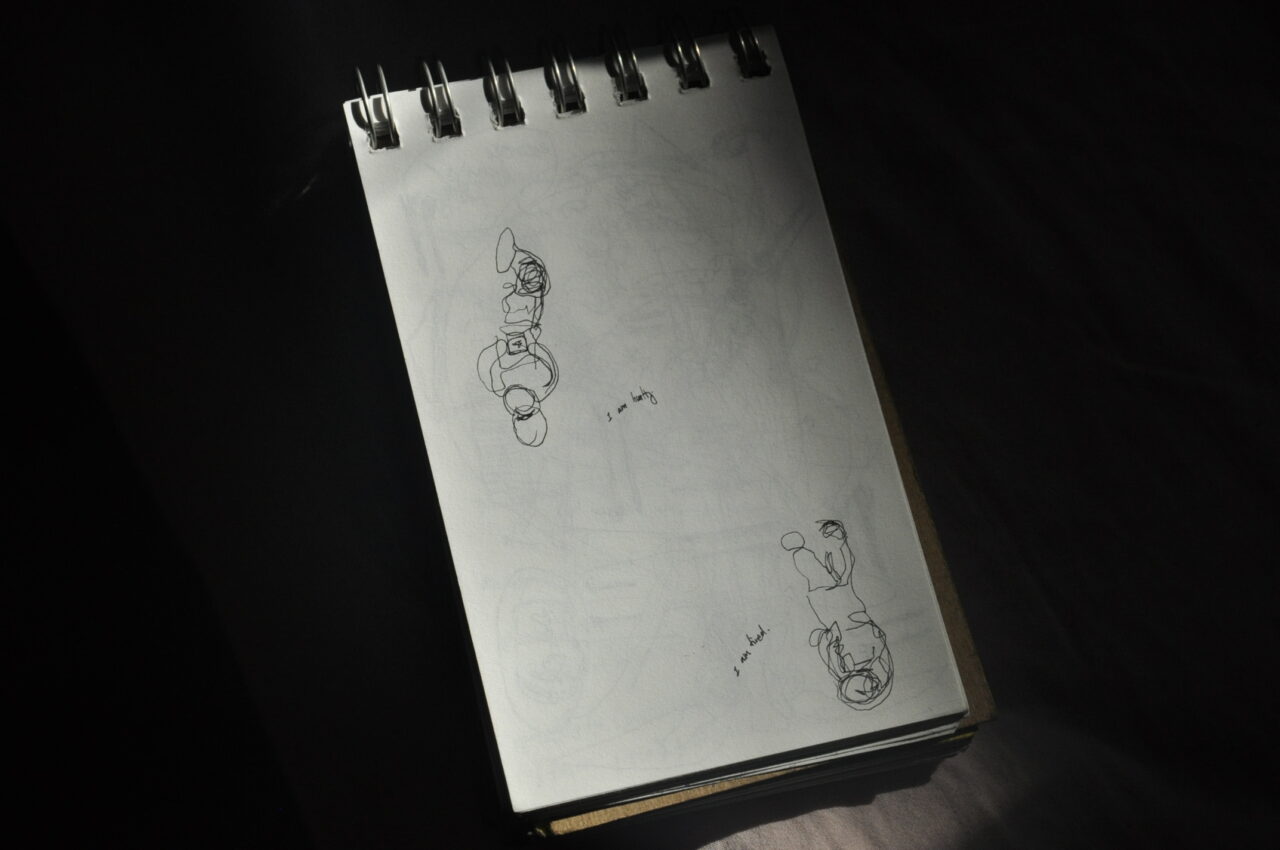

But Taryn quickly found that the pace was not compatible with her recovery or mental health. “I was downright exhausted. My pain was flaring up all the time, it just wasn’t sustainable,” she recalls. “Getting to campus, being in a really stimulating environment— there was a lot that made it really hard to focus and to be in a position where I could say that I was thriving as a student.”

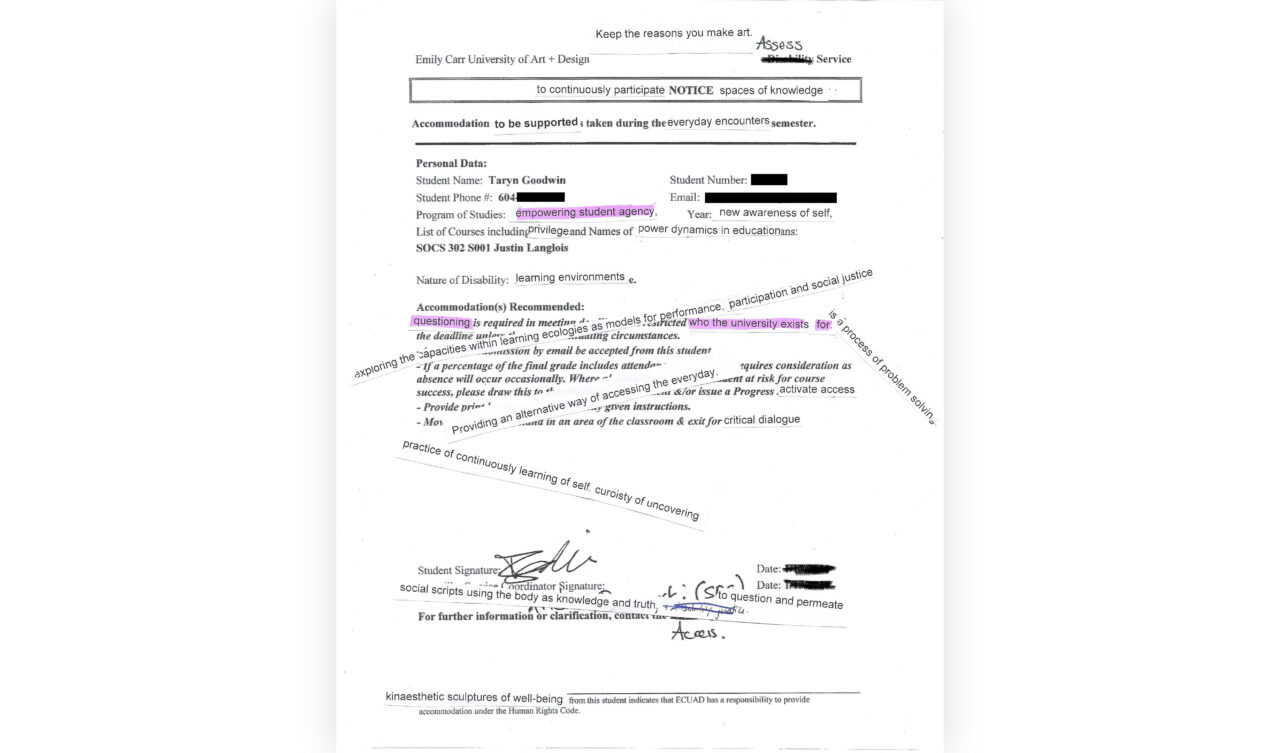

In many organizations, including ECU, the needs of disabled individuals are often addressed through a formal process of accommodations, something Taryn sees as fundamentally limited. “It’s a practice of getting ‘back to the norm’ that suggests, if you can fit in like everyone else, then the accommodation is working,” she explains. “It misses out on so much of the embodied knowledge that people who identify with disabilities have. So I think accommodations for me are sticky because it’s like, ‘we can offer you this and this,’ but it’s still based on able-bodied, normalized, colonial practices of attending a place and a time and a space. I think if accommodations were really created around care, access, wellness, and active listening, it wouldn’t be, what can we give you, but what do you know helps you feel sustained as a learner?”

Since leaving the university in 2016, she spent the next four years working as a consultant to universities through a company she founded, ReFrame Leadership Training. Through her work, she was able to help foster the inclusive disability cultures that she had been missing at ECU.

So when the global COVID-19 pandemic turned university education upside-down, she realized it was an opportunity to finish her degree and build the community she wanted to see.

Remote learning, she explains, “allowed me to actually take care of my health as a student. I could go to a lecture from my couch, have a shower in the middle of the day, eat and lie on my floor when I needed to.” But even though her access had improved, she was still isolated. “I still had no concept of who the other disability or neurodivergent artists on campus were.”

Part of this is due to the way disability accommodations are provided, which Taryn describes as “the confidentiality of access.”

“We treat disability and accommodations as really private and individual. So there’s no way for people to find each other, or to get to know experiences similar to their own. Thus, stigma is built into the avenues of receiving support, and I wasn’t okay with that. I wanted to ask, how could we create a better culture around supporting people with different abilities to find each other, to share lived-experiences and resources, and to organize collectively for a different model of learning, well-being and production that centred the body versus forgot about it.”

Like most students, Taryn began her investigation at the ECU Library. “There are 34 research guides on campus, but none of them were around disability or access or neurodivergence. And so again, there was this gap, even in the book collection… So I was like, well, that is a place to start!”

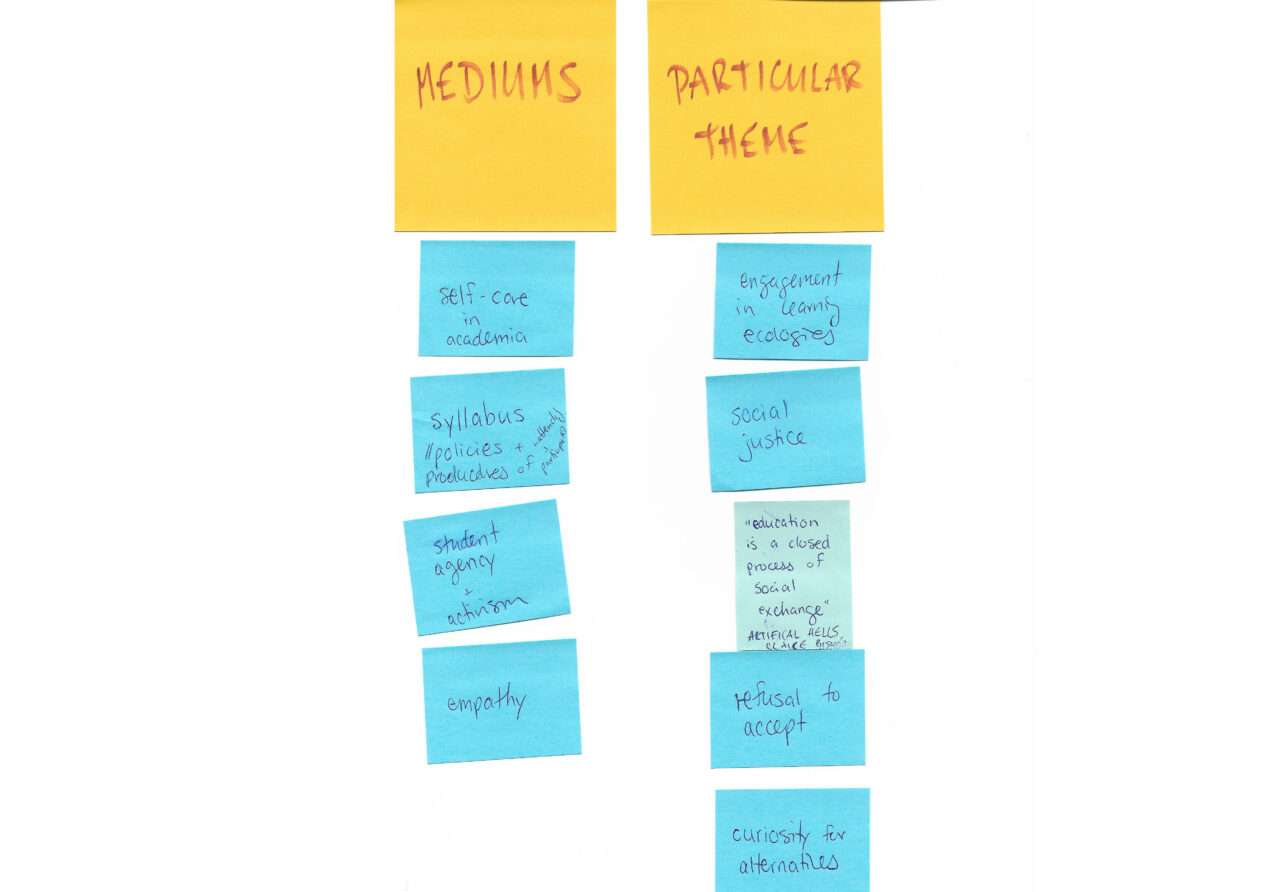

So in the Fall 2020 term, Taryn started thinking about how to address the community element that was missing, and create something that would “sustain that community from a long-term perspective.” She knew she needed more than a 15-week directed study option to do that. So she proposed something novel: a nine-month directed study project, Expanding Disability, that would gather stories from the community, create a lasting archive, and build connections.

She’s already begun the work of compiling resources through her Expanding Disability Community Resource, which anyone can access and add to. She also has an open call for submissions for an online art exhibition entitled CATALOG: The Missing Culture of ECUAD. Any student, staff, faculty member or alumni who identifies as neurodivergent or having a disability is invited to submit through the form.

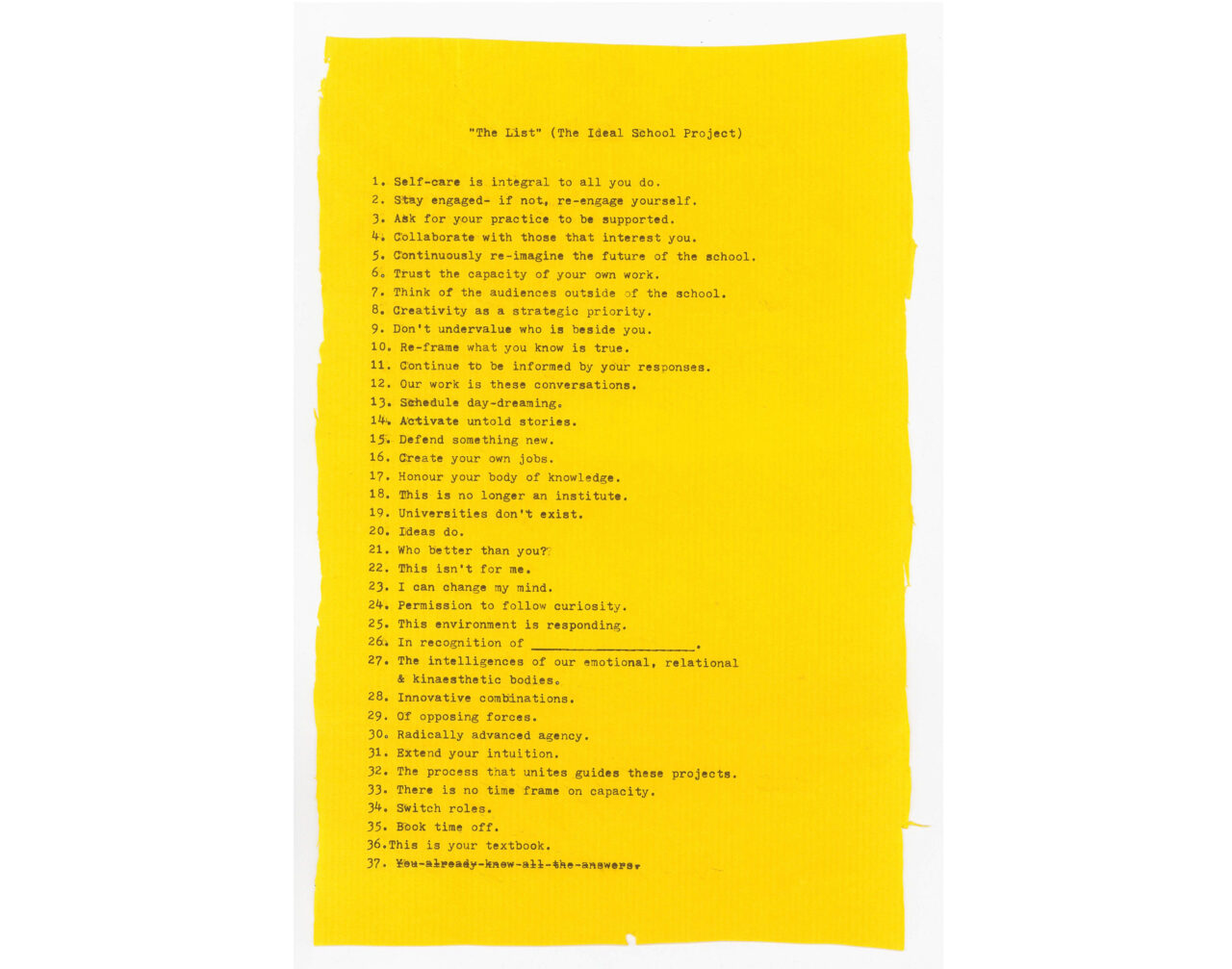

Part of Taryn’s inspiration for this work can be traced back to 2014, when she and her friend Ali talked about what a supportive education could look like.

"I was just going through a really tough time as a student,” she recalls, “And Ali said, what’s an ideal space for your learning? What would it be like? And we just sat there and had this fluid conversation. It was like a poem that came up for me, one thing after another. And she wrote it down by hand, and listened. She held space for me. And now I have this list and this gift of our companionship and connection.”

“I think that’s the practice of community,” says Taryn. “She was able to write something down that I didn't have the space or the mental capacity to write at the time. And she was there, she listened and asked, how can I support this? And I hope that's what this work does. To offer a form of liberation by not hiding one's lived experience. To connect into and from those exact spaces of our identity, that we are so often told to keep silent and not disclose in direct and indirect ways. But to speak them out loud with one another in relationship."

Follow Taryn and her work on Instagram at slow.full.organizing.