Melany Nugent-Noble’s Beacon Project Sets Okanagan Hearts A-Glow

Posted on | Updated

Kelowna residents fell in love with Melany’s participatory artwork When it is necessary to stand still, to the delight of the artist and ECU alum.

Artist Melany Nugent-Noble (MFA 2015) is beaming over the success of her recent artwork that put glowing beacons into the hands of nearly 200 strangers over five weeks in an Okanagan town.

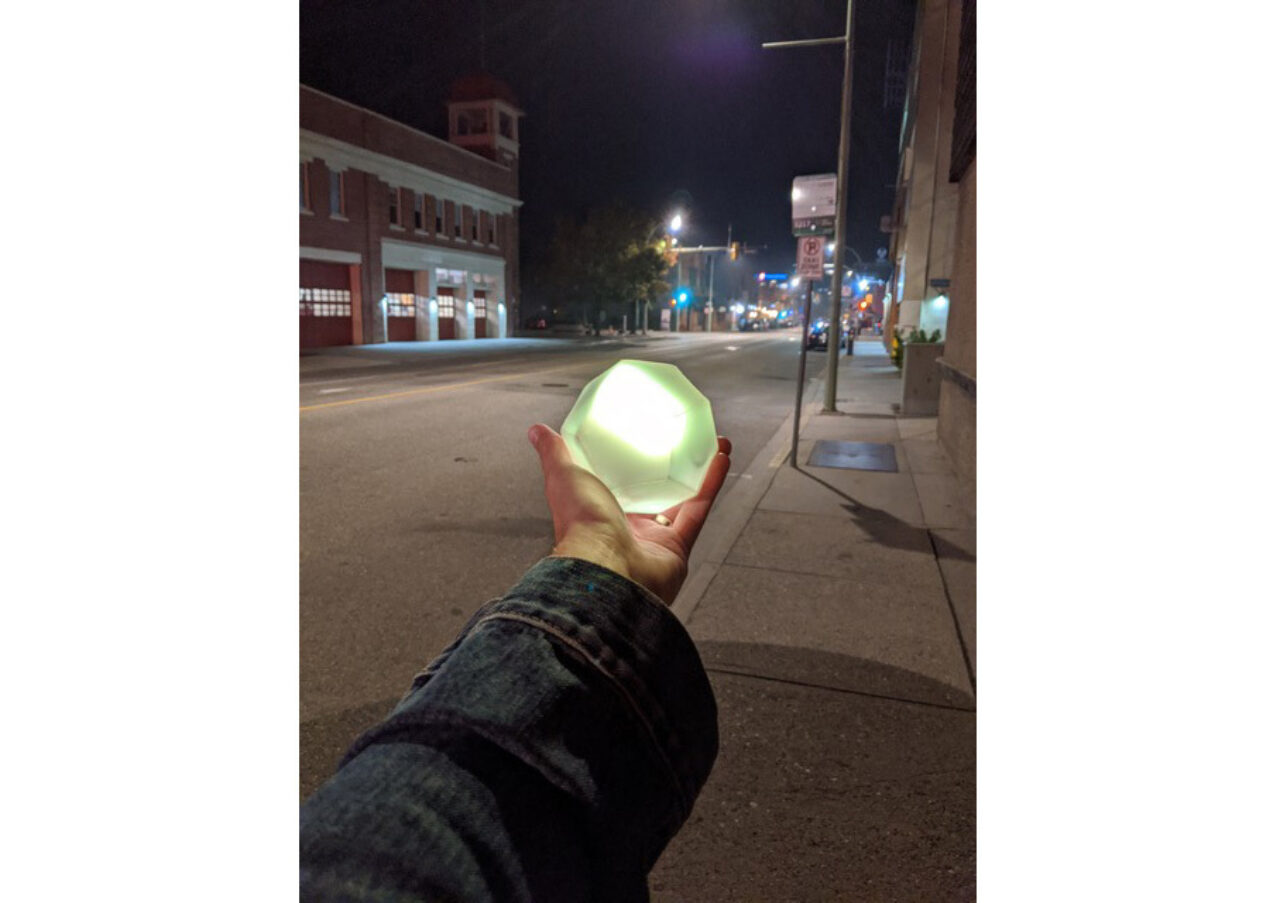

When it is necessary to stand still, Melany’s inaugural artwork as Kelowna, BC’s first artist-in-residence, put volunteers in charge of geometric beacons. When activated, each angular orb glows different colours depending on how close it comes to its sister beacons.

Despite reservations about public reception and public health, Melany says the work unfolded without a hitch.

“The project went incredibly well and was well-received by the community,” she says. “I couldn’t have asked for a better experience.”

When it is necessary to stand still took place between Sept. 10 and Oct. 16, 2020, as part of the City of Kelowna’s public art program. Participants in groups as large as 25 were each given a dodecahedral (made up of twelve pentagons) beacon for three days. After that, they’d return their beacons to Melany to be cleaned and loaned to the next group of participants.

Inside each of the handsome objects is a technological heart; a GPS allows the beacons to locate themselves in relation to one another. As they grow closer or drift further apart, they change colour and become brighter or dimmer. If all active beacons come together, they glow bright white.

Although the work took years to develop, its implicit message took on renewed relevance in 2020.

“One of the primary pieces of feedback from participants was that having a beacon helped relieve loneliness and anxiety amplified by the need for social distancing, and made them feel more grounded and connected to the community,” Melany says. “I received this feedback over and over from folks.”

Participants also reported wishing beacons were available for use on a regular basis. Which was deeply encouraging, Melany notes. Volunteers were not asked to sign a contract or pay a deposit to participate. The only commitment was an acknowledgment of an 80-word statement that reads:

“I acknowledge that participation in this project will include community engagement, both direct and indirect, and that engagement taking place within the context of this project will be done in the spirit of goodwill, cooperation and respect, both towards the beacons that will be given to your care and towards those who you engage with within the community-at-large. This includes ensuring the beacons are maintained properly and returned on time at the end of the activation period.”

Concerns around whether the beacons would hold up over the entire five-week period proved unfounded, Melany reports. While it was “nerve-wracking sending the beacons out for the first time,” not one of the objects was stolen or destroyed.

“Participants treated the project with respect and engagement,” she says. “It was a great practice in trust. That was one of the best learnings from the project as well.”

If dispatches from the participants themselves are any indication, the public widely shared that takeaway. On her website, Melany published some of the participants’ accounts in images or words.

“A simple concept with such profound implications!” wrote one participant. “It was interesting to observe the colours changing as I went about my day and to reflect on my effect on other people (and theirs on mine).”

Another participant wrote, “I found it especially poignant during this time of increased isolation to be reminded of our connectivity and impact on each other.”

A number of participants eagerly adopted the nicknames Melany gave each beacon. In recounting their three days with their beacons, participants would refer to them in as “Agrippina,” “Octavia,” “Marcia,” “Gurance,” “Messalina” or “Lucy” — all famous women of ancient Rome, Melany notes. (Briefly, while writing coding, Melany had begun listening to a Roman history podcast. On a whim, she had started naming versions of her code after Roman emperors. Tiberius is the version the beacons ran on in 2020. To “balance it out,” she named the beacons after women, she says.)

“People did get attached and pick beacons because of their names,” she says. “For instance, one participant picked Julia because that was their grandmother’s name.”

Some participants used the colour of their beacon’s morning glow to choose an outfit for the day. Images on social media reveal beacons in all manner of places. They appeared at the gym; on drives around town; at the office; on a bicycle ride; shopping; at the nail salon; at an art studio; at the curling rink; and, adorably, with several curious dogs and cats.

Some beacons even travelled to people’s most intimate spaces. One participant, identified only as PL, recounts taking the beacon along while visiting their father in a long-term care facility. PL's beacon was nicknamed “Aemelia.”

“Watching my father silently and tenderly rotating Aemelia was by far my favourite moment as she changed from an ocean blue to a white-yellow to a cardinal red,” PL writes. “Although I do not fully know what he was thinking, words were not needed to witness connection and that we are not alone.”

These simple gestures of warmth and ready acceptance suggest the glowing objects spurred an unusual level of attachment.

Beacon-holders created a great deal of “secondary content,” Melany noted in an Infotel News interview. Since Melany developed and built the beacon technology herself, she now also has access to a trove of GPS data generated by the project. (This isn’t personal data, she notes, but rather, simple location data generated by the beacons’ movements). Her next move, she says, is to take that data and find a way to create another public work.

“This project has come together because of — and isn’t possible without — the community,” she told me in July 2020, ahead of the work’s debut. “It doesn’t make sense for this [data] resource to be anything but a community resource.”

Melany says she aims to find funding for future iterations of the project. She is also exploring whether she can make the beacons smaller and more portable. In the meantime, you can dig into Melany’s blog detailing the entire process around When it is necessary to stand still — including a diary of community responses to the work — on her website.