Joy, Imperfection and Humanity in Design

Posted on

Ramon Tejada and Eugenie Cheon on opening up design practice to messiness, uncertainty and diverse ways of knowing.

“My job as a teacher is not necessarily to tell you which way is the right way,” Ramon Tejada, designer and RISD assistant professor, says. “My job is to provide space for you to discover.”

Ramon’s reflection follows a series of workshops during which he led students through a string of exercises designed to “Throw the Bauhaus Under the Bus.” The students in the workshops belonged to a communication design class led by designers and ECU faculty members Eugenie Cheon, Jon Hannan and Cameron Neat.

Creative work can — and perhaps should — be joyful, Ramon continues. Exploring, thinking and creating can be gratifying without being serious or painful.

“This whole narrative of the artist that’s always expiating their sins, and art as difficult and always problematic — I’m saying, ‘No! It’s joyful,’” he says. “As an artist, as a designer, you get to play around with ideas and make things. That’s a huge privilege. We’re making things, and our goal is to engage people in conversation. And you’ve got to take some joy in being able to have conversations through these forms that we create.”

Making space for joy in the classroom, Ramon continues, requires making space for each student as a human being. This, in turn, involves a fundamental rethinking of the teacher as a singular authority figure.

“You have to listen more, which, coincidentally, I think this whole COVID experiment of online learning has helped a lot,” he says. “You also have to slow things down, and pay attention to the students. Be mindful that you’re not teaching a number or an image on your screen. You’re teaching a person.”

This approach transforms teaching into a dynamic, collaborative process, Ramon adds. In such an environment, students are empowered to “make the work they want to make,” or to land in a completely unexpected place. Both approaches need to be viewed as equal to any other, more “classical” way of doing things, he says.

One of the video works made by ECU student Kashish Hukku Jani during Ramon's workshops.

The Playfulness of Design

“It’s one thing to hear about an idea,” says Eugenie, “but to apply it in practice brings learning to another level and depth.”

“Throwing Bauhaus under the bus,” the organizing theme of Ramon’s workshop, is an idea first developed by Ramon and Otis College of Art and Design associate professor Silas Munro. It’s a way of describing a design practice that refuses to be shaped by the outsized legacy of Western thinking on the discipline of design.

From Eugenie’s perspective, bringing this idea into the context of an Emily Carr University workshop helps spotlight how post-secondary spaces are subconsciously defined by Western paradigms. In practical terms, this can mean encouraging students to work in “unconventional” ways, including doing away with the “design brief” — a document that details a design job and informs the entire process from the outset.

“Ramon structured his workshops so that students could actively engage in an iterative process, but with a different, non-traditional lens on their practice,” she says. “For example, letting go of control. Not questioning yourself about whether an outcome is successful. Focusing more on the process, and deliberately breaking away from that question of, ‘Am I doing a good job? Or is this really bad?’ Being free-flowing in their processes.”

Many of these notions have long interested Eugenie. They involve not only learning new practices, but unlearning habitual ones, she says. Having students put these ideas to work is certainly about discovering alternative ways of practicing design, she adds. But it’s also a way of foregrounding the diverse ways of knowing the students themselves bring to the table.

“A lot of our students come from different backgrounds; they carry their own rich and diverse cultural backgrounds, social backgrounds,” she says. “There’s been an ongoing discussion among faculty as to how we bring this to the surface, and integrate this into the curriculum. How can we bolster students? How can we continue to encourage the expression of what might be embedded or tacit knowledge the students might hold, but haven’t yet had a chance to really fully show?”

At one point, says Eugenie, Ramon had all the students turn their cameras to their workspaces. This meant that everyone’s screen suddenly showed dozens of pairs of hands, busily working with their chosen materials. Ramon would put on music to keep the mood up, she says. It felt as though everyone was in the studio together — a feeling that can be tough to cultivate when working remotely.

“It was really fun,” she says, “and it aligned really well with what we were trying to do: bringing back the playfulness of design, not being so constrained by ideas of what is right or wrong.”

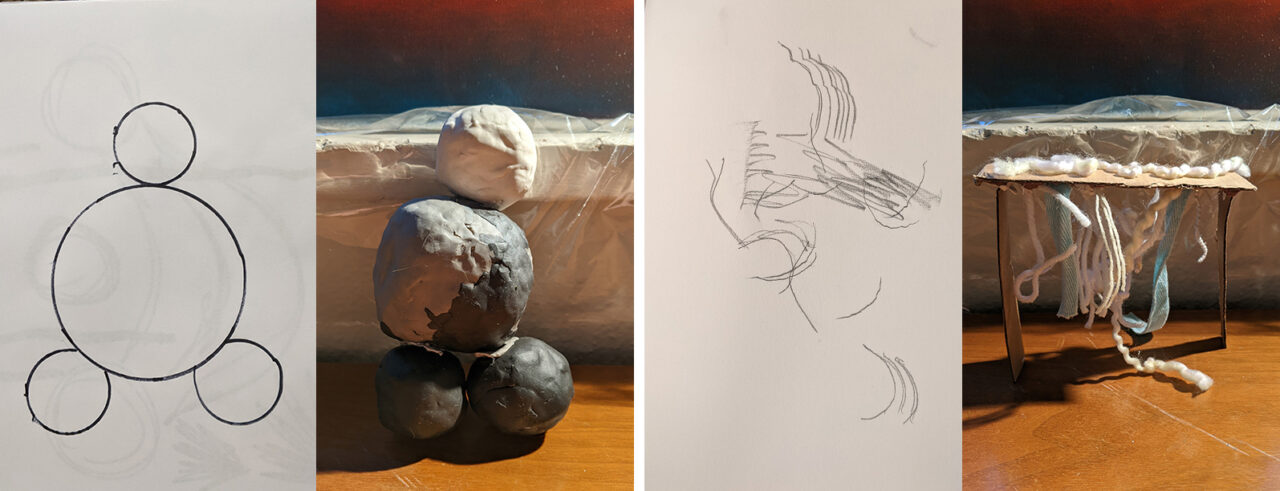

Work made by ECU student Yvonne Zhao during Ramon's workshop.

Letting Go of Perfection

“Ramon emphasized the joy of making — to get messy, experimental, and embrace discomfort in a space of unknowing,” says Yvonne Zhao, one of the ECU communication design students who took Ramon’s workshops.

Yvonne, like a number of her peers, reports having rediscovered design over the course of her time with Ramon. Once “labels such as ‘good,’ ‘bad,’ and ‘ugly’” were thrown out, the practice of design became a place Yvonne found herself flourishing as an individual.

“It was rewarding to make with my hands again, to use tools I wouldn’t typically use, to use them incorrectly, and to completely imbue myself and the stories that are meaningful to me into my creations instead of adhering to target audiences and invisible guidelines.”

Edison Greif, another of the communications design students in the workshop, says he found freedom in the way the workshop reframed design history.

“We had really great conversations about deconstructing the canon and being critical of what we uphold as the epitome of design, and how it’s a very narrow scope without any diverse bodies, ideas or methods of making,” Edison says. The open-ended nature of the in-class work, he adds, allowed the students to let go of any kind of quest for perfection.

“We were surprised to find ourselves getting more and more into the exercises as we went, realizing that our harsh criticality of ourselves and our need to have our work be perfect was, in fact, holding us back.”

The experience of abandoning judgment to focus on process was one Erin Finnerty, another of the communication design students in the workshop, was likewise impressed by.

“We were encouraged to stay in that place, and create in the moment, and see what we could discover about ourselves instead of worrying about the final outcome,” she says. “It took off a lot of the normal pressures we face as design students to always have a critical eye on what we are trying to produce and communicate.”

Communication design student Si Watson’s account of the workshops aligns closely with their peers. The experience was “very grounding,” Si says. They produced work they’re proud of, and “felt very encouraged and supported” by Ramon. But Si worries that applying Ramon’s processes to the rest of their degree doesn’t feel like a realistic goal.

“While this is an excellent way to begin the artistic process, there is often not enough time allotted for this part of the process. It also cannot apply to some projects where we are given a specific audience or a topic we may not connect with,” Si says.

“I will be bringing this [experience] into my personal practice, however, and though it is incredibly difficult to dismantle the perfectionism that lies within me, I will take Ramon’s words with me through every piece in hopes that I will slowly be able to take myself less seriously.”

Kashish Hukku Jani, another of Si’s communication design peers, relates to the feeling that classical design equals having “a box around what you can do with a concept or an idea.” Even aside from trying to solve design challenges, students are often preoccupied with keeping their grades up, or ideas around perfection, Kashish says.

“There are a lot of things going on in your mind apart from the work you’re supposed to be doing with your idea.”

For that reason, she adds, the open-endedness of the workshops was “exhilarating.”

“I explored sound, I explored videos, other mediums and programs that I didn’t think I would explore,” she says. And like Si, Kashish sees ways her perspective may be changing as a result of the experience.

“In the future, with the help of the way this workshop has taught me to engage with different mediums, I feel like my work will have even more dimension. So, more than the end product, it was how this workshop taught me to engage with different processes.”

Bloom and Blossom

For Ramon, making space for joy in design — including making space for the designer as an individual — is part of a much broader conversation. A conversation that is vital, as well as long overdue.

“For art and design, this moment has presented a huge awakening for the conversations a lot of people have been trying to have, but have been blocked from having,” he says. “And I think it’s really great — particularly for students, particularly for students of colour — to see validation of their ideas, validation of where they’re coming from, the way they see things. This moment is allowing for that to emerge, and for it to have space.”

Eugenie adds that she came out of the experience feeling more deeply united in common purpose with her colleagues and students. And she is excited, she notes, to take that feeling forward.

“The workshop really helped us build a sense of community. It somehow made us feel like we were all in the same space. And I really hope to nurture that even further. Because the seed was sown. So, our job now is to make it bloom and blossom. I want it not to be lost.”