Dimeji Onafuwa Designs for a World Where Everyone is Represented

Posted on | Updated

“Everybody deserves their story to be told,” says the Seattle-based designer, researcher and ECU faculty member.

Dimeji Onafuwa is having back pain. While we speak, the designer, researcher and educator gently twists his shoulders and flexes his spine — subtle gestures that are yet visible, even via video chat.

He’s talking about the students in his classes at Emily Carr University when he draws attention to his physical discomfort. Gone are the days of old-school design, he is saying. Gone are the days when bigshot designers could march into a client’s office, announce a solution to their problem, deliver a product and march away, never to return.

That way of working has “created a world that’s riddled with dead objects that live forever,” he says. A wasteland of throw-away products, forgotten and abandoned by their creators.

Designers like his students, on the other hand, want to stay with the work they create, he adds. They want to understand the consequences of the world they’re building. And they know they cannot solve all problems.

Take an acupuncturist, for example, Dimeji says. An acupuncturist would not attempt to cure Dimeji’s pain. They would intervene at a single point.

“Hopefully, that one intervention would allow me to feel better and live better with the pain,” he says. “These new designers are acupuncturists. They are looking for intervention points, and they want to understand the consequences of those interventions they’re making.”

“We design because we seek to alleviate pain.”

Fragility, Frailty, Empathy, Humanity

It soon becomes clear Dimeji’s use of his pain to illustrate a design principle isn’t offered lightly. The relationship between design and the human condition is one he’s considered at great length. That relationship points to some of the core tenets of his design philosophy.

“We design because we seek to understand life,” he says. “And to a certain extent we design because we seek to alleviate pain.”

He points to design educator Cameron Tonkinwise, who asserts that, fundamentally, “humans are frail.” Author Elaine Scarry, meanwhile, in her book The Body in Pain, talks about “the fragility of humanity.”

“That’s where design comes in,” Dimeji continues. “It says, ‘OK, you’re cold. I will make you a coat.’ If we understand it that way, at that fundamental level, design can be seen as a way of understanding how we might live better together.”

Dimeji relates this idea to a concept pioneered by friend and fellow designer Ahmed Ansari called ‘immunological design.’ It refers to how the design of artificial environments can be seen as a way for humans to create a bubble around our fragility.

“Design is very much tied to what it means to be a human and it’s very much tied to how we live,” Dimeji adds. “I feel like we design to make sense of how we live.”

So, what could this mean in practice? Well, says Dimeji, designers typically excel at creating a future that looks different from the present. But very often, in trying to design a future that’s better than the present, they fail to ask, ‘Better according to whom?’

There are as many perspectives on what “better” could mean as there are people in the world, he says. If designers don’t account for that “multiplicity of perspectives,” he says, they’ve fallen into the trap of imagining only one possible future.

“That’s really problematic, because I see design as a way to understand our living together in this world,” he says. “And if we were to live together in this world, then everybody, every participant in this world-making, really deserves their story to be told.”

Designing for the Pluriverse

The practice of deliberately and routinely accounting for these many stories is part of an idea known as “designing for the ‘pluriverse.’” First formalized by sociologist Arturo Escobar in his book Designs for the Pluriverse, this approach aims to establish design as a practice centred around social and environmental justice.

Take UX design (otherwise known as “user experience design”) as an example. UX design is the practice of designing how a person interacts with or experiences a product, system or service. It’s a practice Dimeji both teaches at ECU and engages with professionally.

UX designers, he says, often talk about the idea of “universalizing design,” or, “designing for everyone.” In the context of designing for the pluriverse, “universalizing design” takes on a distinctly different meaning.

“The ‘pluriverse’ is really pointing to the fact that there are multiple worlds,” Dimeji says. “And as you’re thinking about ‘everyone,’ you want to make sure their worlds are represented — not just their needs, but their worlds are represented. For that to happen, you really have to put yourself in their perspective. And it goes beyond empathy. It’s more about carrying them with you and engaging with them in a more connected type of way.”

It can also mean that designing for the future requires engaging with the past.

“We have the opportunity to create the things that will make us into the people we want to be.”

Go Back and Fetch It

Dimeji points to an ancient Adinkra symbol called the ‘Sankofa.’ This symbol, he says, means, “Go back and fetch it.” In other words, to understand where you’re going, you must understand where you’re coming from. But when peering into the past, we must do so with a critical eye, Dimeji adds. The past as we know it is only one possible story from among an endless number.

“I often reference that African proverb, ‘Until the lions have their historian, the story of the hunt glorifies the hunter,’” Dimeji says. “There’s a story of the hunt that’s been told that is not quite correct. So, we are going back into the past and correcting the story. And then we’re using that corrected story to reimagine the future. In other words, the past isn’t wrong; the past is simply not fully representative.”

In Seattle, where Dimeji lives and works, he co-founded a collective of designers and researchers called Common Cause Collective. One of their projects involved working with the City of Seattle and BIPOC community leaders to “map out” a more inclusive city. Over a series of workshops, the group built a design for “a new version of Seattle where all voices are heard, and where BIPOC communities, BIPOC cultures are sustained. A version that is more inclusive as opposed to exclusive.”

This involved a great deal of work researching and rethinking the history of Seattle. Specifically, it involved being explicit about how the voices and stories of BIPOC people have been excluded from the telling of that history. Meaning the group grounded a more inclusive vision of the future in a refigured past.

“We assume that the past was the only past that existed. But now, going back and redefining that past can provide us with an opportunity to redesign design,” Dimeji says. “Anne-Marie Willis said, ‘The things we create turn around and create us.’ So, we have the opportunity to create the things that will make us into the people we want to be.”

Beyond Inclusion

Take remote learning, for example. Clearly, remote learning has its disadvantages. Being denied face-to-face contact is one of them. But pandemic pressure has opened doors as well, says Dimeji. It has provided opportunities for seeing the world from a different point of view.

Toward the end of our conversation, I tell Dimeji that designer Ramon Tejada, during a recent interview, noted how remote learning represents a chance for teachers and schools to reconsider how they define accessibility. Some disabled students, for instance, can experience barriers or be entirely excluded by “normal” in-person class requirements. Since the move to remote learning, some of those students report being able to participate far more robustly in online classrooms.

“I would even broaden that and say remote learning allows us to practice inclusion in a different way,” Dimeji says. “I always talk about ‘beyond inclusion,’ and ‘expanding the boundaries of inclusion,’ and ‘designing for difference.’ And I think designing a course really has to do with that, too — thinking about all the different students and all the potentialities, all the potential needs and concerns they might have, and designing a course that addresses all of those and allows students to feel comfortable engaging in the course and participating at different levels.”

Inclusion, says Dimeji, is too often shorthand for bringing the historically excluded “other” into “the centre.” In this scenario, no fundamental change is made to the system of exclusion. Assumptions about what is “normal” and what is “abnormal” are upheld.

“Beyond inclusion” proposes a worldview that acknowledges the existence of multiple centres. This acknowledgment overturns the false dichotomy between inside/outside, normal/abnormal, self/other, he says. It proposes that individual perspectives exist along an infinitely complex spectrum, rather than inside or outside of frameworks defined by Western history. In doing so, it undoes the power of that colonial history to continue to shape the future.

This, he adds, is very much what it means to think of the pluriverse as a “world where many worlds fit.”

Principles in Practice

“How has all of this resonated with students?” I ask Dimeji.

“They’ve been wanting to talk about these issues; they struggle with them,” he tells me. “They really want to learn about the ways in which they can own their practice, and they want to design responsibly. One of the things I share in class is a work by Allan Chochinov who says, ‘Designers are in the consequences business.’ Students want to understand the consequences of the work we’re doing.”

That’s where Dimeji’s job as an educator comes in. He can help his students understand the consequences of their work. He can ensure his students’ design decisions are appropriate for the problems they’re confronting.

I later consider how neatly Dimeji sidesteps patting himself on the back — an opportunity I’d left wide open for him in asking my question. Fortunately, some of his students were aiming to do that work themselves.

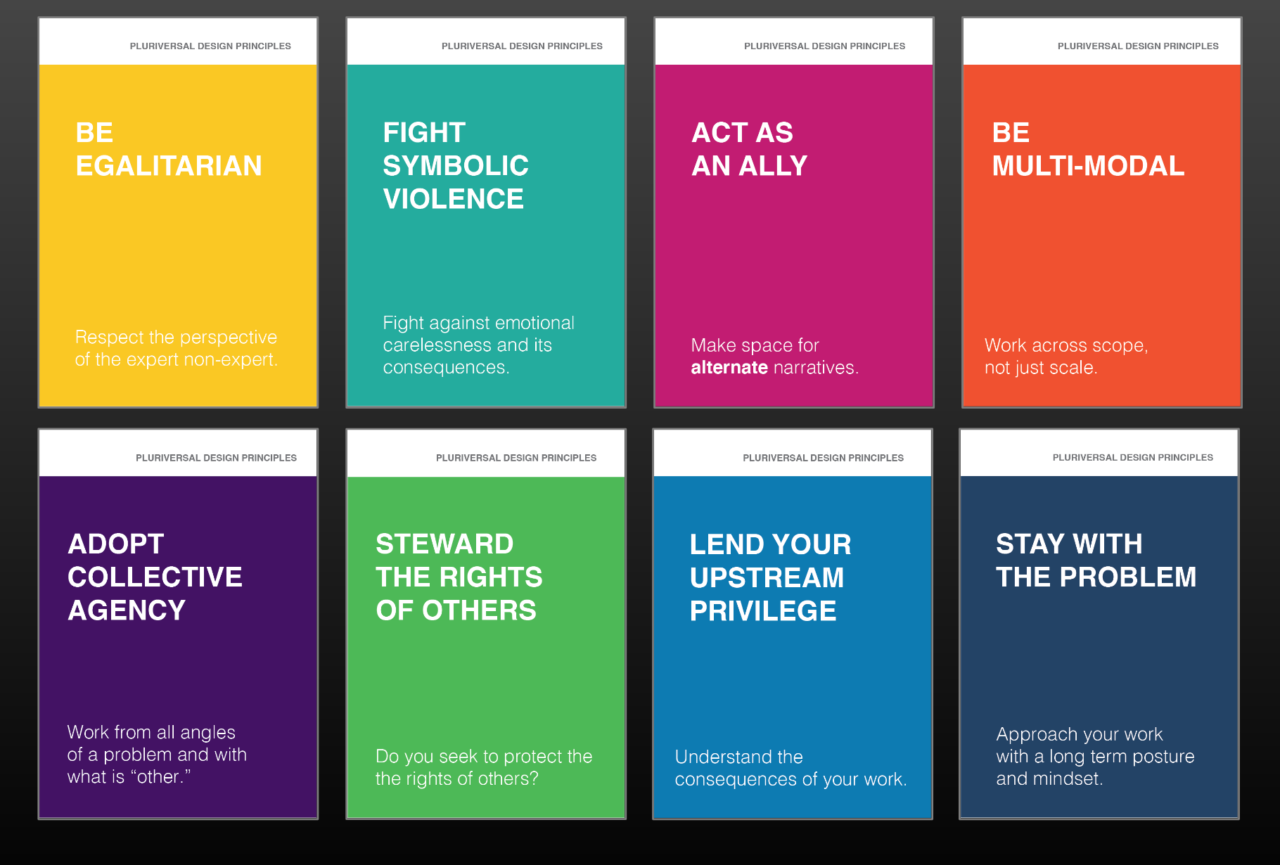

Dimeji provides his students with a list of “Pluriversal Design Principles” at the start of semester, he explains. These principles are meant to stand as a “provocation;” a catalogue of ideas to which students can return regularly.

A few days after we speak, an email lands in my inbox. Included is a note from students of his Fall 2020 third-year design course. The note, to my eyes, is nothing short of remarkable. It details an expression of earnest gratitude for Dimeji’s teachings, which his students say provided an opportunity for growth “not only as designers but as people.”

But the attachment is the real jaw-dropper. His students had gathered remotely over winter break to create their own pluriversal principles. Included are incitements to “Question Your Worldview,” “Lead With Compassion,” “Be Human,” “Be Rigorous” and “Consider All Life and Beings.”

And what does Dimeji make of this work his students undertook, even after their course had ended?

“This,” he says, “warms my heart.”

--

You can find links to Dimeji’s writings, plus resources for further exploration of many of these ideas (and more) on Dimeji’s website.