How Designing with More-Than-Humans Fosters Social Change and Environmental Justice

Posted on | Updated

Teaching design to help heal a broken relationship between human beings and the rest of the planet.

For much of history, the practice of design has been preoccupied with making lives better for the Western, modern white male, Louise St. Pierre tells me via video call.

Your clothes and shoes, your apartment, your city, your coffee mug, the headphones you plug into your ears, and, of course, the device you’re using to read this now. Someone designed all of it, she says. And for most of the world, those objects and items may have been designed for someone who looks nothing like them. This holds no less true for the non-human world.

Given the overwhelming influence design has on the world and our experience of it, what if changing how designers think is one of the keys to healing a broken relationship between human beings and the rest of the planet?

Sound grandiose? Maybe. But as Louise and Zach Camozzi, a Health Design Lab and DESIS Lab researcher, fellow designer and ECU faculty member, explain, this work of changing design occurs in exceedingly subtle ways.

In fact, as students learn in Louise's third-year ‘Design with More Than Humans’ course and Zach’s second-year ‘INDD Core Studio-Design for Biodiversity’ course, it starts by attempting to look at the world through the eyes of another being.

From a second-year Industrial Design studio project which tasked students with proposing ideas for rockfish habitats to support rockfish conservation.

From Stuff to Sustainability

“If designers start to design for nature, with nature in mind as a priority emphasis, then automatically, without even really knowing it or seeing it, we’re disconnecting from the priorities of modernity and industry,” Louise says.

Both she and Zach are industrial designers, she reminds me. And that means they were trained to produce stuff. In fact, design practice as we know it links back to the Industrial Revolution, she notes.

“Industry is all about making money from extracted resources, and mowing down trees and taking things out,” she says. “Design has emerged from that. So, now we have this whole set of skills and knowledge and perspective, and we’re realizing, ‘Oh, wait a minute. This isn’t sustainable. Or ethical.We need to redirect all of this.’”

In practice, “redirecting” can mean many things. For instance, as part of a multiphase inquiry into ocean health on BC shores, students in the second-year Industrial Design studio were tasked with proposing ideas for rockfish habitats to support rockfish conservation. But it quickly became apparent that nature designs rockfish habitat perfectly well on its own, without help from humans. Instead, what rockfish need from humans is better policy and regulation to protect existing habitat from human impacts.

The aim of “designing for rockfish” thus quickly shifted. It was no longer about creating a better or more effective product. Rather, it became an exercise in understanding the complex and alien ecosystems of underwater beings. And sometimes, that means knowing when humans need to get out of the way.

There are virtually no realistic scenarios you can imagine where you are not directly in contact with — if not entirely surrounded by — the products of design.

And you’re not the only one whose existence is shaped by design, Louise continues. The impact of human industry and ingenuity extends across species. It even extends across categories, she notes. Just look at how energy infrastructure and transportation design affect forests, waterways, animal migration, landscapes and the atmosphere.

From a second-year Industrial Design studio project which tasked students with proposing ideas for rockfish habitats to support rockfish conservation.

Animism and Designing with More-Than-Humans

“We are trying to reset the assumption that designers are only working for people; designers are working for all the beings on the planet,’” Louise says. “This is an animist perspective. Suppose we understand animism as acknowledging the agency of all beings. In that case, we can still design, but now, as we’re designing, we’re thinking about the needs of other beings, the needs of ecosystems, the needs of the Earth. And this desperately must happen.”

An animist perspective doesn’t place the world’s creatures above humans, Louise adds. It asserts that humans have been given priority for too long. Through this lens, the world is an interrelated web, “rather than something that is managed or controllable or human-directed,” Louise says.

And in the context of an interrelated web, all players have an equal stake.

The work of encouraging designers to seek perspectives outside their own is an aim shared by some of Louise and Zach’s colleagues. One such colleague is designer, researcher and educator Dimeji Onafuwa. Dimeji notes that, very often, in trying to design a better future, designers fail to ask, ‘Better according to whom?’

“That’s really problematic because I see design as a way to understand our living together in this world,” he told me in February. “And if we were to live together in this world, then everybody, every participant in this world-making, really deserves their story to be told.”

For Zach and Louise, “every participant in this world-making” includes not only every person but every rockfish, every stone, every tree and every plant.

Another such colleague is artist, designer and associate director of Aboriginal Programs at ECU, Connie Watts. Connie, who is of of Nuu-chah-nulth, Gitxsan and Kwakwaka’wakw ancestry, attended several of Louise’s classes in Spring 2021. And according to Louise, she played a vital role in illustrating for students how equity and inclusion can inform the design process.

“Connie’s role was really important to us; she came in sometimes to listen and then at other times to offer a sharing circle,” Louise says. “She spoke from a place of personal knowledge; she talked about respect for all life; gratitude to all beings; how all forms of life are energy. The perspective she offered was profoundly important to all of us.”

From Yutaan Lin’s wild rice ritual design project.

Speaking Streams, Wild Rice and Cedar

In January, Louise’s students chose a “being” to work with. Part of their challenge over the semester would be trying to understand the worldview of their being.

One student, Yutaan Lin, chose wild rice. He researched the plant’s life cycle and ecological contexts and created a system map. (A system map is a diagram showing how elements of a system are interrelated.)

His research included an exploration of how Indigenous and non-Western food cultures view wild rice. He looked at practices around planting, harvesting, processing, buying, preparing and cooking the rice. He also learned how to support the plant itself as a living being.

As a result, Yutaan designed and prototyped a “rice ritual” to help people situate themselves in a “position of equity” with wild rice. In doing so, he aims to foster a culture of gratitude around eating wild rice — an idea that shares a lot in common with the concept of mindfulness. (As noted in numerous studies, mindful eating promotes individual health and encourages sustainability in local and global food networks).

By prompting participants to consider human questions “through the context of more-than-human eyes,” Yutaan sees potential for such rituals to help fundamentally reframe people’s relationship to food more broadly, as well as to politics, culture, ecology and one another.

From Julia de la Puente Calvo’s Language of the Stream design project.

Another student, Julia de la Puente Calvo, chose to focus her design attention on a specific stream. Some of her early studies involved prototyping things like garbage bins and information panels. Julia identified these items as a kind of infrastructure of “care” — a framework of familiar objects to cue feelings of responsibility or even stewardship in passersby.

Her research eventually honed in on the “language” of the stream, which she often visited multiple times per week during semester. Like Yutaan’s research into wild rice, Julia’s examination of stream-language performs a subtle overturning of the typical hierarchy between human and non-human.

“Language is how we share,” Julia writes. And while non-human beings also share with one another, humans insist on a distinction between human language and the communication codes used by other beings. But this distinction, she continues, doesn’t indicate the way the world works; instead, it demonstrates the limits of the human imagination.

“It can be very hard to wrap our head around the idea that a stream has a history, relationships, or a time of its own, but it does,” Julia writes. “In the same way we have written our history on the walls of caves and paper parchments, the stream has written his history onto what he has touched, left untouched, or buried. His history can be found in the rocks he has moved, the rocks he has kept, the trees he has grown and the trees he has tumbled.”

From Julia de la Puente Calvo’s Language of the Stream design project.

A third student, Gina Mae Schubert, explored the meaning and importance of the cedar tree. Starting with her understanding that the cedar is an ancestor to human beings, Gina developed a number of strategies for encouraging relationships of respect and intimacy between human beings and the forest.

Among them, a series of yoga postures for what she terms ‘Tree Rapport Yoga,’ and a Forest Listening Blanket which promotes physical closeness between humans and trees during extended periods of contemplation or meditation. A member of the Haida Nation, Gina Mae also developed a Haida Formline cedar image, which she plans to embroider onto the listening blanket.

“The human is born after the tree, and is reliant on the tree for all of their existence,” Gina Mae says, noting cedar nourishes a spectrum of human needs including physical, social and spiritual. “From an Indigenous perspective, this includes ceremony and medicines. From a non-Indigenous perspective, this is shelter, water and air.”

Her designs reflect a desire to foster a deeper understanding of that holistic relationship, and to encourage reciprocation via acts of human care. Gina Mae writes that she envisions “a utopian future, much like our Indigenous past, where we listen to the forest and the earth; where we live in balance with nature and respect for all sentient beings; living in a trading system for human physical needs; and where we are brought back to reality thorough ceremony.”

She has since gone on to work with Julie Andreyev and Maria Lantin on the latest iteration of their Wild Empathy project, called Branching Songs, which aims to build empathy for the 1308 trees slated to be cut down to make way for the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion.

Gina Mae Schubert’s prototype Forest Listening Blanket, folded and ready for transport into the woods.

From the Margins to the Mainstream

These are not conventional design projects by any stretch of the imagination. But that may be changing. Five years ago, Emily Carr’s design faculty and DESIS Lab were more or less alone in exploring and advancing these ideas. But the international network of DESIS labs has since followed suit. And increasingly, these ideas are being adopted by designers and researchers around the world.

And not a moment too soon.

Science tells us that human industry has brought the world as we know it to the brink of collapse. The ocean is heaving with plastics. Carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere continue to skyrocket. An already shocking rate of species extinction accelerates, as does broader environmental degradation.

For designers who wish to help haul the environment back from the edge, altering the planet and its systems no longer makes sense. Instead, design should support changes in human behaviour. It should intervene on behalf of other species. Which isn’t to say there is no place left for traditional design, Zach notes.

“Students can step back into traditional forms of design” he says. “But they need to be exposed to new — and neglected — ways of working, or else we’re just going to continue making stuff.”

In other words, ecologically responsible, sustainable design must engage with non-human (or more-than-human) beings as co-creators. Educating students in these new ways of working can be part of a decisive shift within both design and every industry design touches.

“When students leave the program and advocate for a more-than-human being in a professional context, initially there will be barriers” Zach continues. “But this shift in perspectives is necessary. And it might just redefine a business’s approach.”

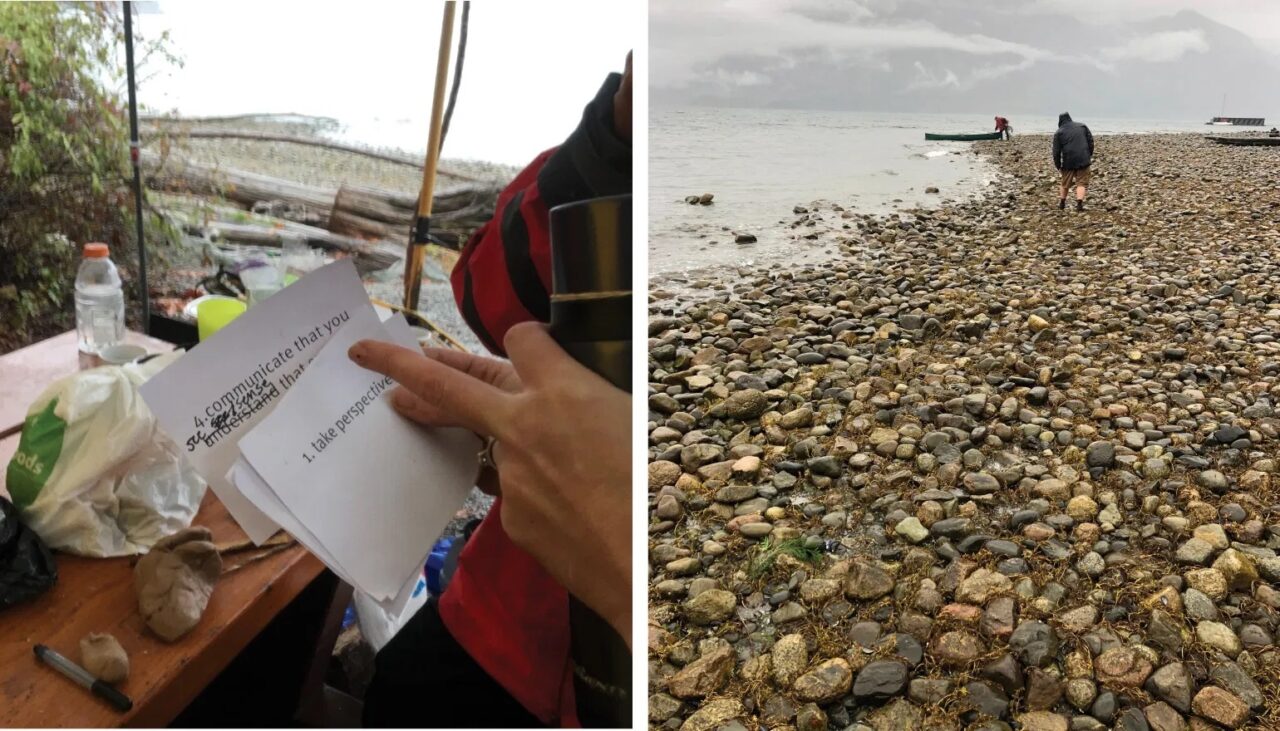

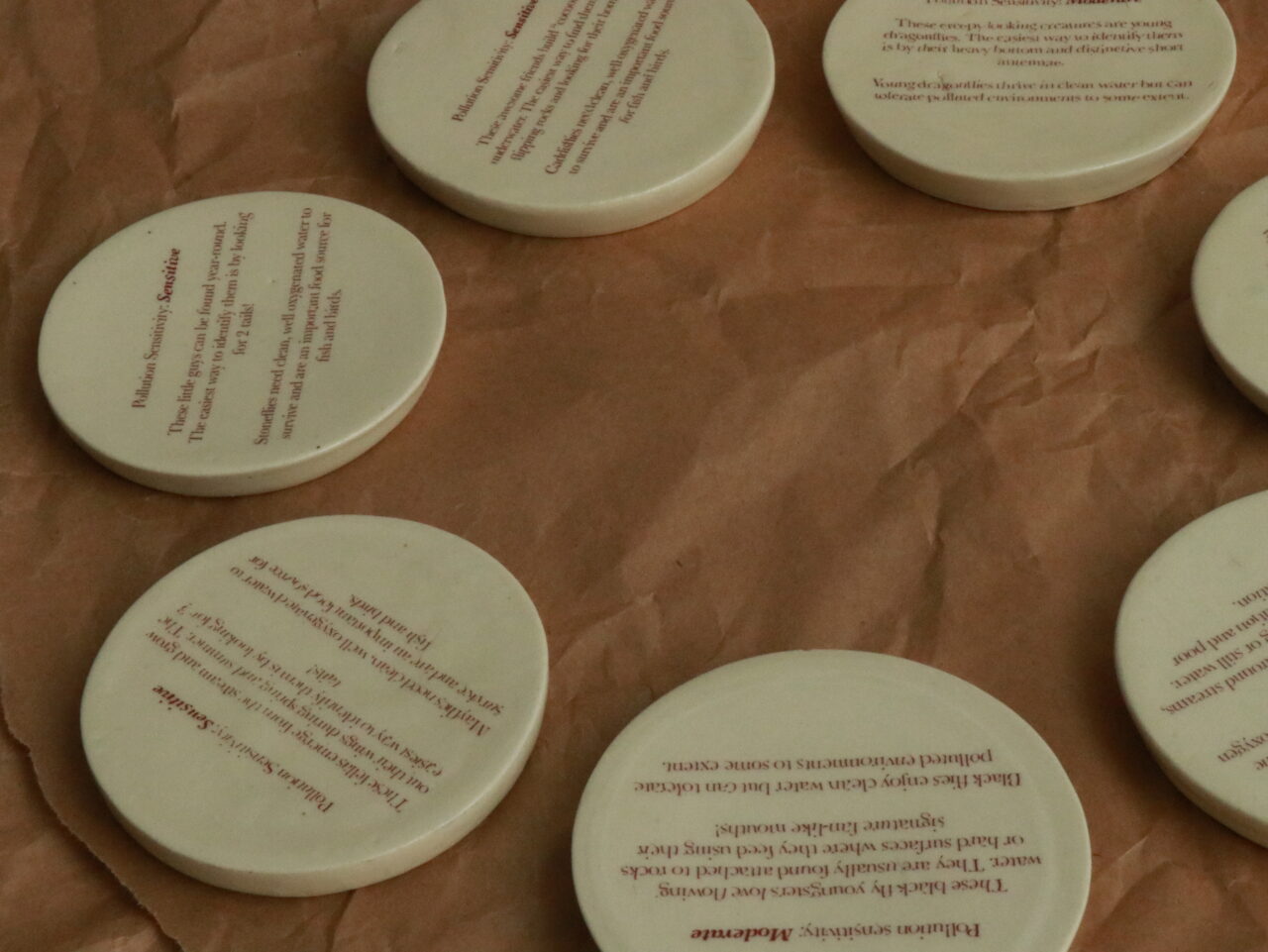

From Zara Huntley’s 'Design for Biodiversity – Contextual Inquiry at Barnet Marine Park and other Coastal Region,' via the DESIS Lab at Emily Carr University.

Culture Shift

In describing their work, Louise and Zach use words including ‘ecology,’ ‘biodiversity,’ ‘remediation,’ and ‘conservation.’ These are not necessarily the first words that come to mind when we think of design, I tell them. More often, this vocabulary is associated with the world of science.

Louise doesn’t hesitate for even a moment before replying. Science is critically important, she tells me. But in terms of how it affects people’s daily lives, science has its limits.

“Sometimes people listen to science, and sometimes they don’t,” Louise says. “But design affects everything, every day. Every bit of our lives, our responses to things, our media, and all our human-made places are influenced by the stuff around us. All of it is designed as a cultural activity. And it is a change at the level of culture that is so gravely needed.”

--

Louise’s third-year course ‘Design with More Than Humans,’ and Zach’s second-year course ‘INDD Core Studio-Design for Biodiversity’, will be offered again as part of ECU’s Fall 2021 course catalogue. The Design for Biodiversity series is made possible by an Ian Gillespie Design Research Grant.

You can read more about the many projects and events coming from the DESIS Lab at Emily Carr University on their website, desis.ecuad.ca.