Bonne Zabolotney Teaches Communication Design for Climate Change

Posted on | Updated

The designer and ECU faculty member is asking how design can provide clarity, insights and strategic approaches to understanding — and combatting — climate change.

Bonne Zabolotney knew from the beginning that teaching communication design as a tool for helping combat climate change would put her and her students out in the wilderness.

“Prior to running my course this past spring, there wasn’t really a source of ‘communication design for climate change’ practices that I could just Google and see, ‘Here’s how other designer educators are doing this,’” Bonne, a designer and ECU faculty member, tells me.

Students in Bonne’s COMD310 core studio course would have to make their own definitions for the practice of ‘communication design for climate change.’ Fortunately, Bonne says, the students were more than willing.

“And the different kinds of communication design that came out of often very similar issues that students were grappling with — it was pretty astounding. So, we now have a starting point to build up this design practice.”

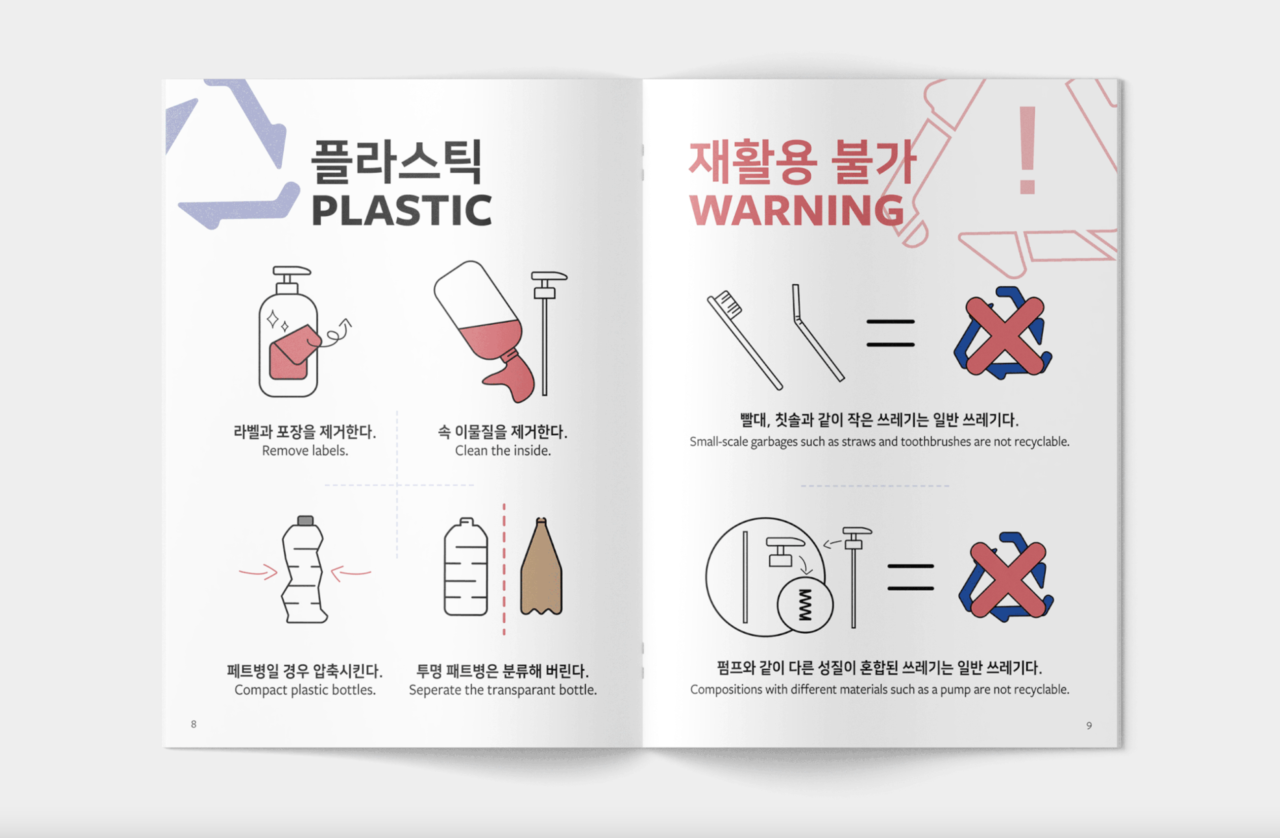

From Anny Lee's Korean Waste Sorting Guidebook, a booklet aimed at helping the elderly in Korea reduce household waste by simplifying the recycling process.

Localism x Globalism

As with any fledgling subject, ‘communication design for climate change’ held a number of surprises in store for the class. One of the first major revelations came very early on. Bonne had originally intended to focus on “localisms” for the first part of class — a focus that would see students think about the context of their own, personal world. The second part of the class would deal with “globalisms,” meaning those larger systems that are more complex, “wicked problem spaces.”

But Bonne and her students quickly realized their COVID-safe remote-learning setup meant people were “attending” class from all over the world.

“While we had a few students in Vancouver talking about systems they could see locally, they had classmates who were touring blue-jeans factories in Pakistan,” Bonne said. “The local and the global suddenly became very close, very much closer together than I ever anticipated. It was no longer a binary.”

This turned out to be a “gift of online teaching,” Bonne says. Students were able to see their familiar, local contexts through the eyes of classmates living thousands of miles away, and were brought into close contact with ways of life that were unlike their own.

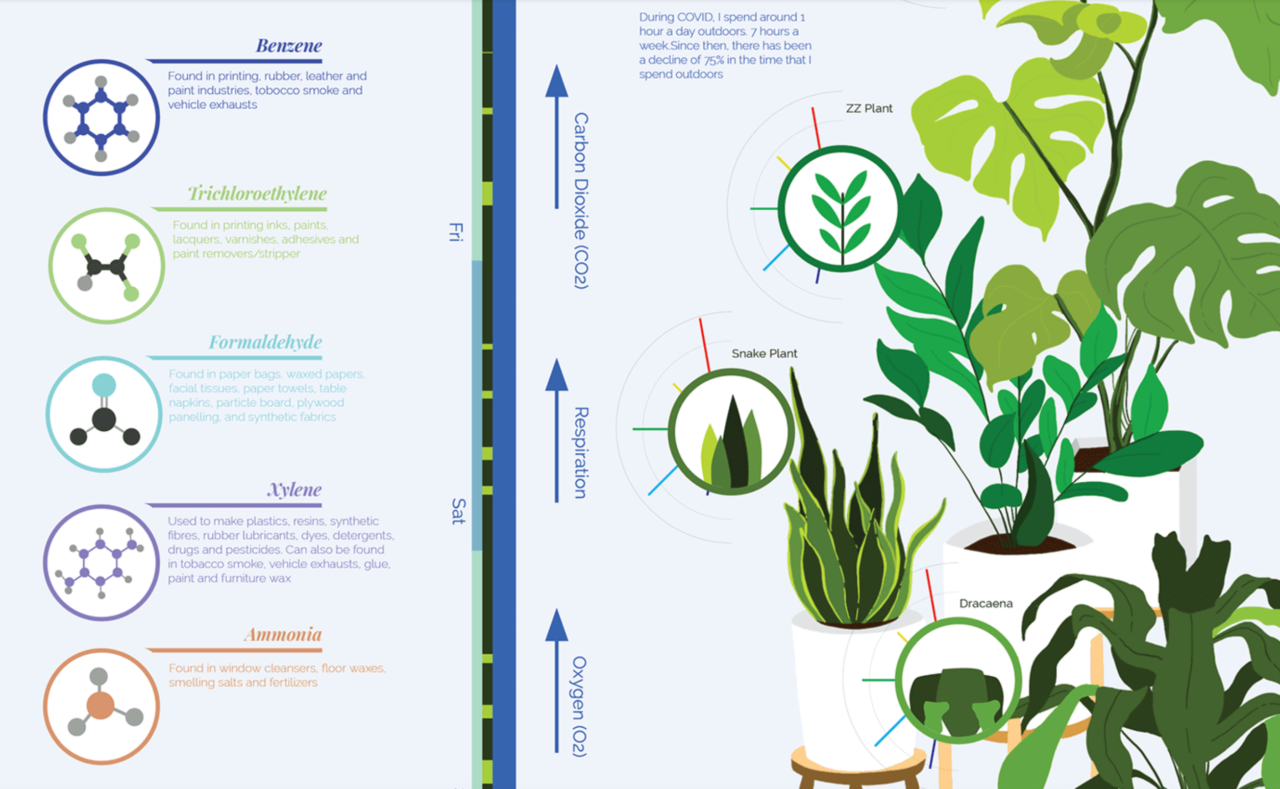

Leo Cho's The Air: Personal Consumption Audit looks at air quality, air's constitutive parts, and how all of it relates to human health.

Personal Consumption Audit

As eyeopening as this experience was, it also risked being somewhat overwhelming, Bonne says. Check-ins were a regular part of the course, as was a more general emphasis on wellness.

“Partly, that meant remembering that we’re third-year communication design students. We’re not ready to solve all the problems. In fact, this moment can be about making observations and understanding our own participation in a world that is facing climate change.”

Developing this understanding involved a “personal consumption audit” — an exercise aimed at helping students focus on one piece of the climate change puzzle that felt both appealing and approachable.

Some students decided to look at the energy consumption represented by screen-time. Others looked at personal water consumption including drinking water, laundry, bathing, gardens and plants. One student, Leo Cho, performed an audit on the air itself, looking at its quality, its constitutive parts, and how all of it relates to human health.

In each case, the audits saw students identify how meaning can be made of data where it exists, and where ambiguities exist that need clarification. By establishing a clear direction for their design research, students avoid being crushed under the weight of the broader problem of climate change.

From Hannah Franes' documentary Looking Into Glass, which demonstrates the huge amount of waste generated by her family’s window-making company in her small hometown.

Daylighting

Bonne notes that the personal consumption audit is not meant to imply that if people simply try hard enough, their individual choices could change the fate of a warming globe.

“I think there’s enough literature out there around climate change to know that it’s a corporate strategy to place responsibility on individuals,” Bonne says, “because then we’re so busy trying to figure out where to drop off our styrofoam that we don’t question the companies that are manufacturing it. The point of the consumption audit is for students to find an entry point into understanding systems.”

Nor does a narrowed focus mean ignoring the larger, systemic forces at play. She points to the language around civic recycling programs as an example of an issue that is both approachable and symptomatic of the larger issues around climate change.

A typical city webpage about recycling might show a classic three-arrows diagram, with a sentence noting, “We get rid of anything that’s not clean.” But Bonne says a huge number of questions cascade down from that statement once it’s probed even superficially.

“First of all, what does it mean to ‘get rid of’ something that’s not clean?” Bonne asks.

“That seems like a huge flaw in the process. It’s easy for things not to be clean in a city with a million people recycling their yogurt containers every day. And then what, exactly, does ‘not clean’ mean? As communication designers, we’re looking to daylight out these problems a little bit, and interrogate them further.”

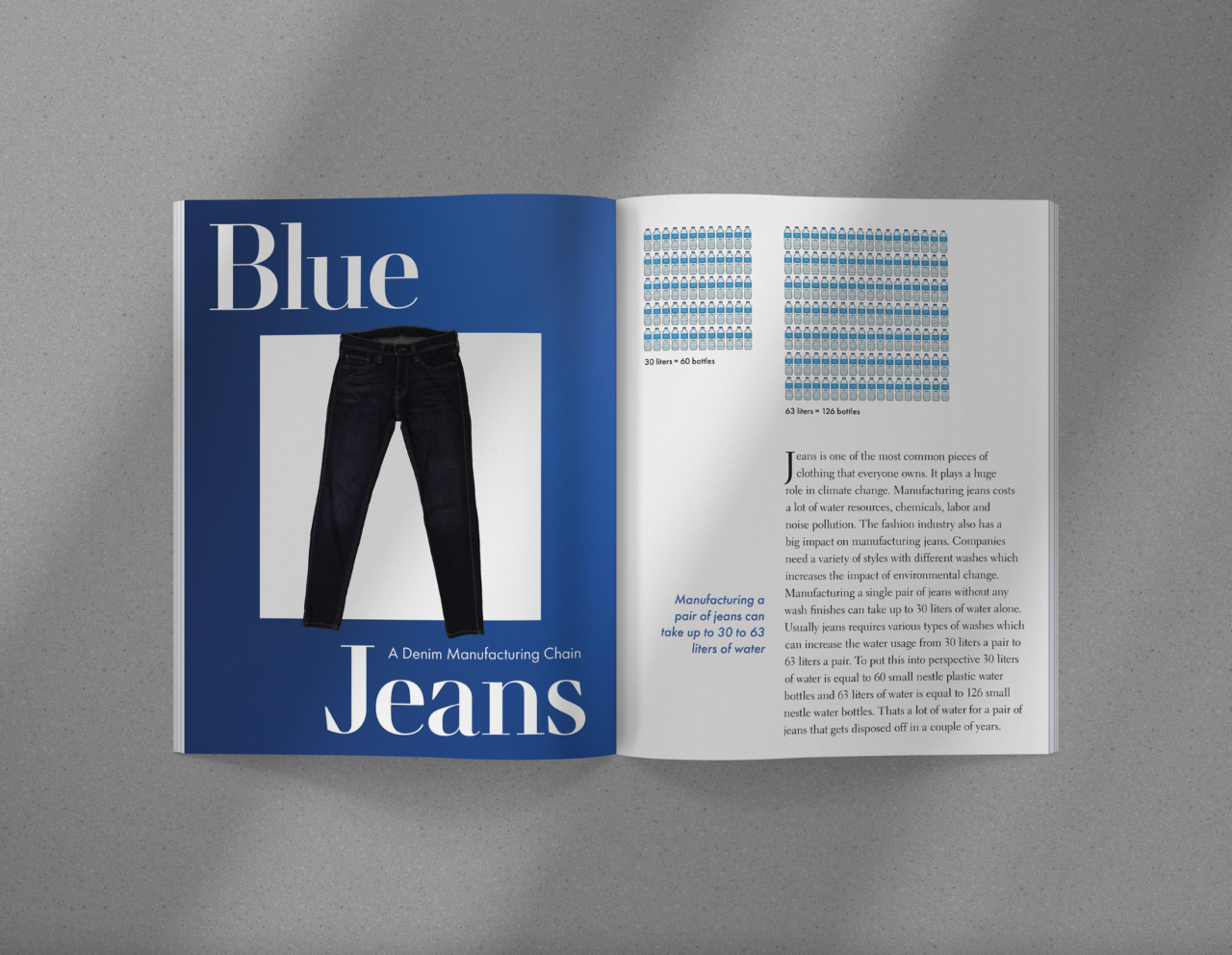

From Zara Imran Hassan's project Blue Jeans: A Denim Manufacturing Chain, which explores the social and ecological costs of the denim industry.

Tussle with What It All Means

As Bonne had hoped, “daylighting” meant very different things for each of her students.

Student designer Zara Hassan looked at the outsize environmental impacts of the blue-jean industry, using photos she took personally during a visit to a factory in her hometown of Karachi, Pakistan. Zara’s classmate, Anny Lee, created a booklet aimed at helping the elderly in Korea reduce household waste by simplifying the recycling process.

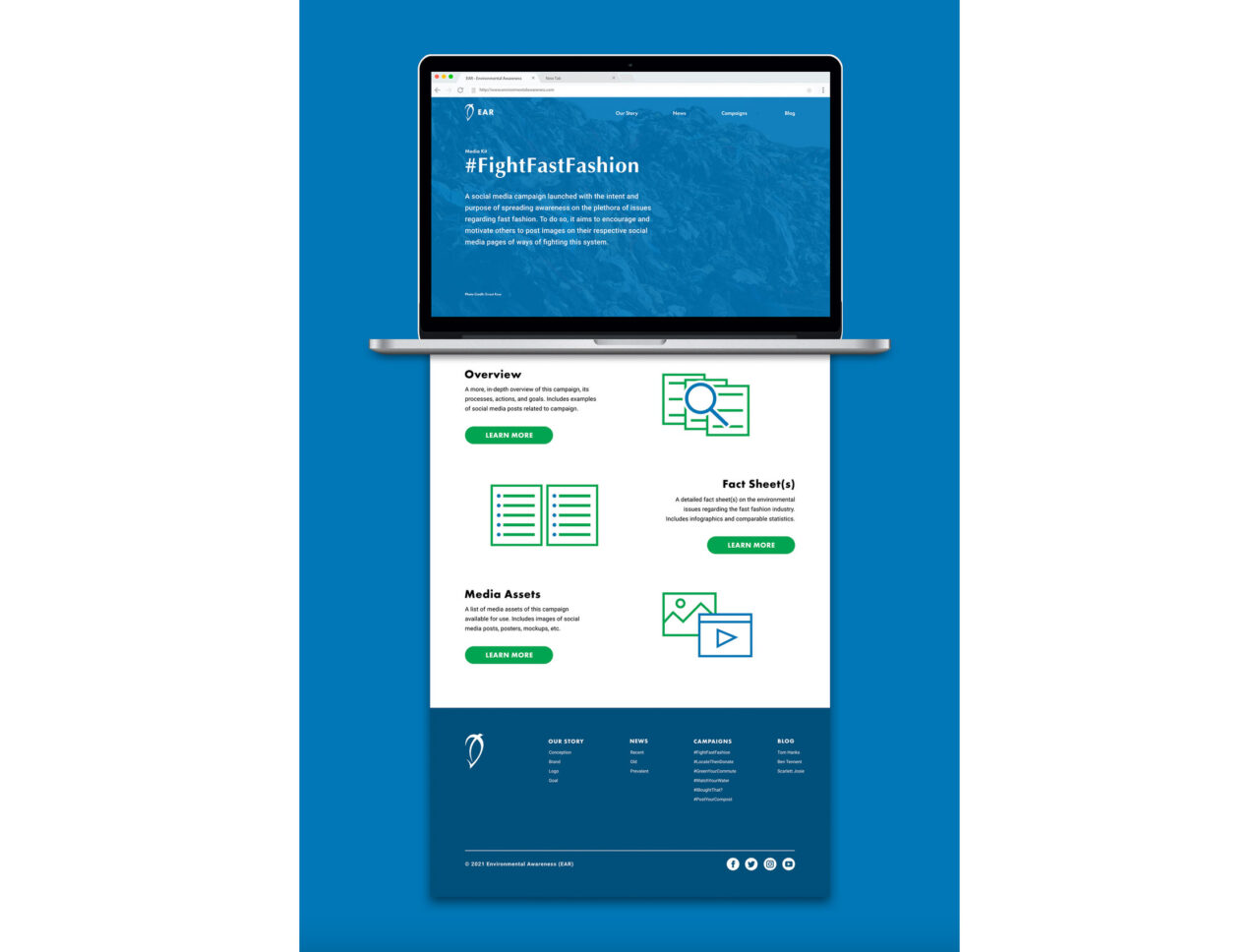

Owen Xu created a media kit to help “fight fast fashion” by spotlighting the environmental harms of the industry, and offering solutions for how to help mitigate them. And student Hannah Franes developed a prototype for a documentary that demonstrates the huge amount of waste generated by her family’s window-making company in her small hometown.

Bonne emphasizes that communication design, especially as it relates to climate change, doesn’t necessarily have to solve every problem it identifies.

“We’re here to make processes more transparent; to call into question how these processes are being represented, which creates space for other designers to say, ‘What is it that we should be doing? What should we be knowing? What effect is our work having on consumers, on manufacturing, on recycling?’ Bonne tells me.

“As communicators, we try and puncture holes in these representations to bring the underlying issues to light, so we can tussle with what it all means.”

From Owen Xu's Anti-Fast Fashion media kit, aimed at problematizing and offering solutions for waste generated by the fast fashion industry.

Prototyping

That ability to expose underlying issues is one Bonne would like to see designers hired for more often. Designers are more than just aesthetes who can make something look good, or help make a marketing campaign more effective. Designers are also skilled investigators who can understand complex systems and the consequences wrought by minute changes within those systems. They’re also natural deep-diggers, with a passion for nuance and detail.

“We want our students to learn to be excellent communicators who can, in fact, also be excellent researchers,” Bonne says. The trick, then, is to encourage institutions and organizations to take advantage of those research abilities.

“For a city to have a design researcher on staff — that’d be pretty amazing. Or to have a designer who works with policies, because policies are simply written practices. We can prototype policies and anticipate their impacts and map them and design them or probe them.”

The first step, Bonne says, is to spur wider interest in communication design for climate change. With that in mind, she’s reached out to colleagues both in Australia and the United States in the hopes of sparking collaboration.

“We need to expand the respect and understanding about what communication designers are capable of, and that would include working in policy, working in non-aesthetic ways,” she says.

“Until we establish this as a practice, we’ll make mistakes. We’re still prototyping, though, and watching for when it really starts to develop insights.”

Bonne’s COMD310 Communication Design for Climate Change course will be taught again in Spring, 2022.