Kirk Gower and the Romance of Painting

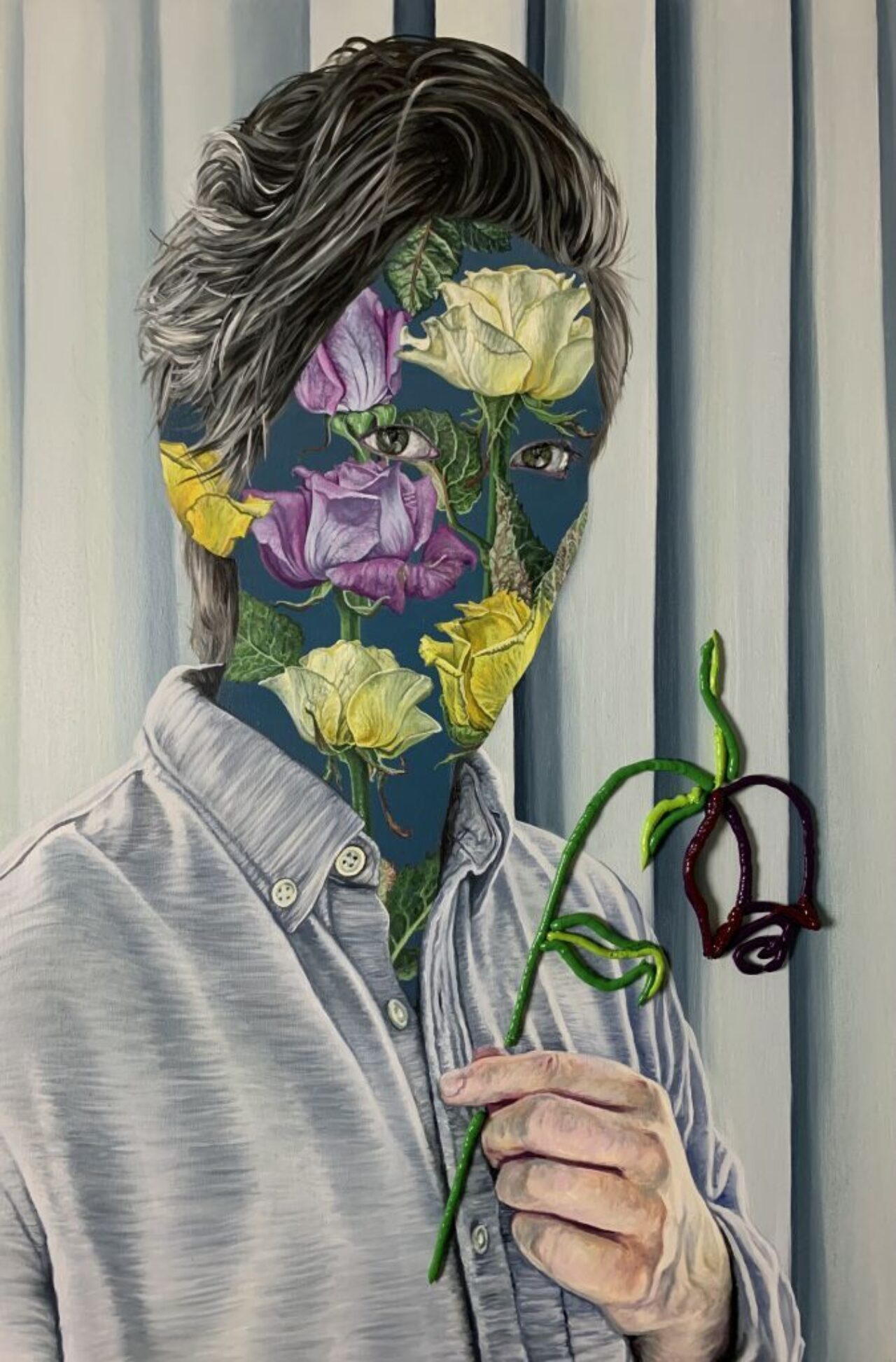

The Return of Spring, 2020. (Image courtesy Kirk Gower)

Posted on | Updated

The alum discusses the points in his practice where femininity and queerness collide in order to confront and challenge the viewer.

Kirk Gower (BFA 2010) explores queer identity in his contemporary portraiture. The highly rendered works of art are interrupted with impasto paint graffiti, flat patterns and protruding sculptural flowers made of paint. Kirk handpicks the elements in the paintings to emphasize emotion in the figures and confront the hierarchy of queerness.

The paintings highlight queer bodies, often in fantastical spaces. His work is both surreal and dreamlike while the viewer is repeatedly forced to acknowledge that it’s a painting. Kirk’s work has incorporated abstractions from yearbook graffiti to flat patterning to interrupt the surface of the work.

“Even a year ago, my work didn’t have quite as many layers as the recent body of work with the introduction of pattern and flat, matte colours,” said Kirk. “These elements can be viewed as a window pane. It provides an additional realm within the painting, something you can peer into that simultaneously exists with the image while remaining separate.”

Kirk Gower, Imaginary King, 2018. (Image courtesy Kirk Gower)

Kirk’s paintings have layers upon layers of meaning.

“Pattern has become a way to also introduce a romanticism layer into the work,” explained Kirk. “Whereas the impasto is a way of breaking the image altogether. I use it as a technique to remind people of what they’re looking at: it’s fabricated, constructed, paint.”

A lot of people fall for the hierarchy of painting and the medium itself. “I’ve always been quite confrontational in my work even when it’s passive,” laughed Kirk. “It’s always meant to pull the viewer out from the allure of the work itself, it will always remind them it’s a painting.”

The elements Kirk adds on top, especially the impasto, also tell the viewer something. These queues provide further context for the work, whether comical, grotesque, shocking, fun, cheesy or romantic. “The impasto always has a bit of fun even with other queues,” said Kirk.

Kirk Gower, The Fall of Me, 2020. (Image courtesy Kirk Gower)

While Kirk’s paintings often deal with masculinity and queerness in contemporary portraiture, they also address femininity and romance. These elements collide on the canvas, prompting uncomfortable viewers to question where the discomfort comes from.

“When looking at queer culture, there’s an idealization over masculinity as the perfect queer man,” said Kirk. “I don’t feel that I fit that.”

“We all have those tropes and notions of what it means to be in love,” said Kirk. “A lot of that is derived from romantic comedies. I’ve taken those cliches that we are so used to seeing and placed them on top of constructed, masculine figures. The juxtaposition is quite interesting.”

Kirk continues in saying that he wants the viewer to understand that it’s okay to have a feminine viewpoint, especially in love and romance. “I want them to question why this conversation makes them uncomfortable,” said Kirk. “Fundamentally, I want to ask people to question why seeing a man with feminine-associated symbology around him such as hearts or flowers makes them so uncomfortable.”

Kirk explains that the people in his paintings are real people from his life.

“They’re queer people that I see on a regular basis in my day-to-day life,” said Kirk. “When I post the work online, that gets skewed and lost in translation. There’s a whole group of people in queer culture that aren’t as represented as they should be. It’s important for me to add to the diversity of queerness by using real queer bodies.”

Kirk Gower, All I See is You, 2020. (Image courtesy Kirk Gower)

Often young artists get hung up when they’re still in art school on developing a style or finding their voice, which can take time.

“When I think about my painting when I was still at ECU, it was so much more uptight,” said Kirk. “It was insecure. I was so young when I was in school, the level of maturity wasn’t necessarily there. As a young artist, it’s frustrating to hear it takes time, but it really does. Being ten years out of school, I’m now more confident in my skill, content and voice in this world.”

Kirk points out that so much can change in ten years, including what you’re interested in let alone how you actually create work. “It’s inherently still connected,” Kirk says, in reference to the work that you do during school. “My identity has evolved just as much as my practice, but that very early student work still has relevance for that time, just not in 2021.”

When it comes to advice upon leaving school, Kirk reminds young artists that it’s okay to have a day job. “Having a day job means I never have to compromise my artistic vision,” said Kirk. “I can make the work I want to make, that I’m passionate and excited about. It doesn’t matter if it sells or not. It’s more fulfilling than making commercial work or landscapes for the rest of my life.”

In closing, Kirk shared knowledge he received from faculty: “It’s funny, Landon Mackenzie gave some of the best advice and I never took it seriously until looking back on what I do now. She said, ‘You have to be a vampire to a certain degree. One day you may have other obligations, a family, a job. The minute those things are done, you need to pull out your art. You may not even have a studio; you may be doing this in your kitchen. Fundamentally, you’re doing it and it’s going to be late at night.’ And I remember thinking it was never going to be me, but it exactly is.”