Michelle Chan on the Power of Participatory Design in Health Care

Posted on | Updated

The 2020 grad uses participatory principles to craft design that grants young patients more agency.

Michelle Chan (BDes 2020) could change the world.

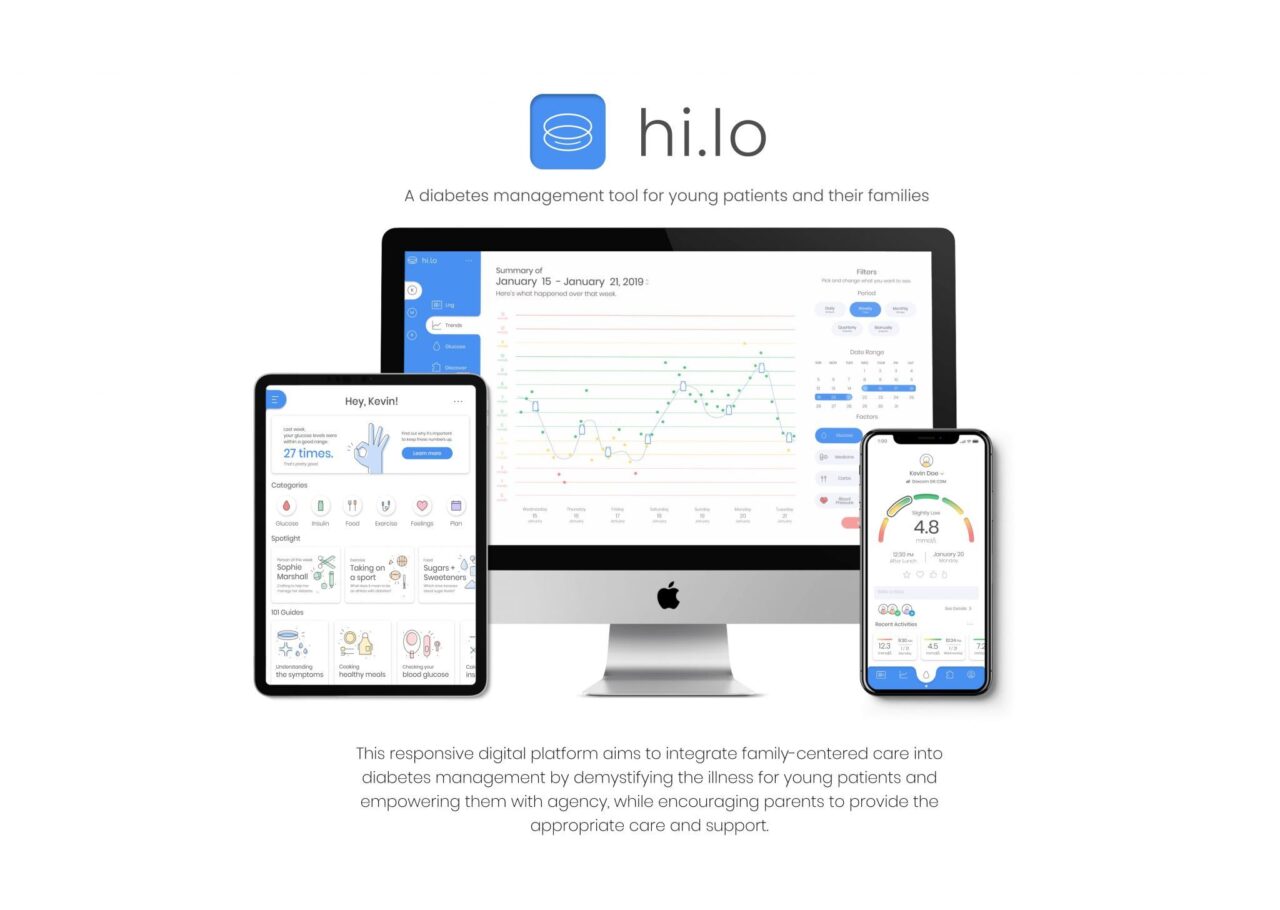

She has a passion for participatory health design, and her grad project hi.lo (pronounced high-low) demonstrates this as it provides a framework to allow children and teens diagnosed with diabetes to be involved in their own healthcare.

“I was looking into children’s health in my third year and contemplating the spaces in that sector I could design for,” Michelle said. “I had a lot of elaborate ideas, but what really stuck out to me in my brainstorming process was my first experience encountering a chronic illness.”

Michelle explains that as a child, one of her friends and classmates was diagnosed with diabetes and on reflection it made her think about the experience of being diagnosed and how that changes life for both the child and the family.

“The more I researched, the more I realized that the majority of resources available were not created with the child in mind, but just for the parents,” she said.

“While that is understandable because the parents are the caretakers, the young patient should also be involved in their healthcare from early on.”

As Michelle reminds us, a diagnoses of Type 1 Diabetes is an autoimmune disorder and a chronic illness – it doesn’t go away, so the child will be dealing with it for life.

“Designing for children allows them to be the main participant in their own health,” Michelle said. “It gives them agency over their body and a greater understanding of their own health.”

In designing the web and mobile application, Michelle said she had to consider what it meant to include a child in the design process. “I wanted to create both roles and a design that age appropriate,” she said. “The first visual was a bumblebee motif which didn’t go over well.”

Michelle’s design for hi.lo is playful and round to appeal to a younger audience but isn’t overly cute and remains sophisticated. “Children’s content has been cartoonish with a Comic Sans style font for some time,” said Michelle. “This design was tested and created in part by my co-designers.”

Michelle emphasizes that participatory design is crucial to her process. “I invited individuals who were diagnosed with diabetes as children, as well as parents and teachers to participate in the development of my project,” she said. “Knowing that personal health conditions are sensitive topics for some, I was concerned that nobody would come forward to discuss or participate. After reaching out on social media platforms, I was surprised to see that the diabetes community was more than willing to share their time and experience for my project.”

Little did she know, what she thought were just participants in her research would later become a supportive team of passionate co-designers. “After learning and implementing participatory design, I wondered why I would ever do this another way,” said Michelle. “I’m not saying other ways of designing aren’t as effective, but researching this way was so much more effective.”

hi.lo could potentially change the life of a young patient with diabetes but it’s not available – yet. “I would like to see this come to fruition,” said Michelle. “I have thought about ways to work with those in health care or diabetes research who may a vested interest in this project existing in a tangible way.”

In terms of designing another project for the health care industry, Michelle says that first and foremost she looks for gaps in accessibility. “Everyone should have access to health care and while accessibility is a really large umbrella, it still shows you who is left out. It’s easier said than done, small changes and adjustments alone take a long time,” said Michelle. “Everyone needs to be able to understand what’s going on with their healthcare. If you speak a different language than your doctor, how adequate will your care be? If you can’t hear your doctor, how adequate will your health be?”

Michelle points out that accessibility also looks like navigation maps for those with mobility issues to know what the best and more efficient way to get around a building is. “It also looks like having information about health and healthcare being web accessible,” said Michelle. “Like information about Covid being in the palm of your hand, filtering out misinformation.”

“The technology is there but the process takes longer,” she said. “It sounds smaller than it is to get this available.” Digital healthcare has come so far, but there’s a long way to go.

In working with the Vancouver Coastal Health on MyGuide Concussions, Michelle learned that there is a balance between the aesthetic and the functional. “So often there is something that is really pretty to look at but it’s not functional, it’s not accessible,” said Michelle. “You have to design for all walks of life with health, not just a niche group of people.”

On winning the ECUAA Community Engagement award for her project hi.lo, Michelle said that it gave her a sense of closure for her degree. Michelle and her peers were in the middle of finalizing their layouts for the grad show, wrapped up in the excitement of the pending graduation celebrations, when the pandemic hit.

Michelle detailed what it was like when the news hit. “I remember getting the email when things were getting cancelled. I was in a food court and just started crying but also laughing, it was hysterics – everything was just happening all at once.”

Although there was an immense sadness of missing out, Michelle shared that she’s also proud of herself and her peers for completing their degrees and persevering. “We made it through,” she said. “It wasn’t easy.”

“Without convocation and the grad show, getting the ECUAA award really signalled that my degree was over. That was my grad,” said Michelle. “It also validated choosing participatory design methods. It was really rewarding to be acknowledged through my work. This award also belongs to those who participated in the design process with me, because this project wouldn’t have existed without them.”

“It gave me the confidence to move forward as a UX/UI designer,” she concluded.