Gwenessa Lam on Art-Making and Uncertainty

Posted on | Updated

“I'm always interested in questions that don't have an answer,” say the artist and new ECU faculty member.

Art-making provides an ideal space in which to grapple with uncertainty, says artist Gwenessa Lam, who recently joined Emily Carr University as Associate Professor in Painting + Drawing in the Audain Faculty of Art.

On the heels of a return to Vancouver after several years as Assistant Professor, Painting and Associate Chair of the School of Visual Art at Calgary’s Alberta University of the Arts, Gwenessa took a moment to reflect on how a relationship to the unknown is a through-line in her multidisciplinary practice, even as that practice continues to change and evolve.

“I'm always interested in questions that don't have an answer,” she says. “At the heart of any project that I do, I’m always questioning what it is I'm looking at. That's the question that often begins a project.”

Throughout bodies of work including Shadows, Landfall, Interiors and Windows, Gwenessa’s concerns have often revolved around plumbing the reaches of psychological space between the individual and the objects and environments with which they most intimately identify — in other words, “questioning what it means to have a place called home.” Lately, however, Gwenessa says she’s turned her focus to historical objects and artifacts, and “how we understand ourselves through history.”

Gwenessa Lam, 'Corner Shadow no. 2,' 2010. Oil on canvas.

This shift is visible in the work she contributed to a 2019 exhibition, entitled Imagining Fusang: Exploring Chinese and Indigenous Encounters, at the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria. The show took as a departure point a Chinese legend about a 5th-century monk named Hui Shen, who sailed to a land he called Fusang, which 18th-century mapmakers placed at the 50th parallel along the coast of what is now known as British Columbia.

Responding to this speculative history of early connection between Chinese and Indigenous communities, Gwenessa created a series of drawings and photographic prints of historical objects of ambiguous origin, linked by an absence of certainty around their stories. These works, she notes, are aimed at creating an opportunity for viewers to reflect on the ways in which history is proposed as a didactic for present-day complexities and interrelations.

“The work isn’t really about the object per se, even though the work is representing it; rather, the work is an entry point to think about the engagement we have with this little historical artifact,” she says. “And it begins to echo some of the more complicated relationships that we have with real bodies and the ways in which we understand and even categorize ourselves, oftentimes problematically.”

In reading through scholarship around such historical objects — objects that remain without any kind of definitive taxonomy — Gwenessa says she immediately began to see parallels with contemporary struggles to define power, who has it and who is denied it.

L: Gwenessa Lam, 'Saturna Island Ceramic Figure.' Photographic Print. | R: Installation view, 'Imagining Fusang: Exploring Chinese and Indigenous Encounters,' at the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria. Works by Gwenessa Lam.

“The parallels I see involve a tension around how we're framing institutions and racialization,” she says, adding such dynamics are often embedded more deeply beneath the surface when it comes to historical objects, since ideology can be concealed under the guise of pursuing greater “knowledge” or “understanding.”

“Because of that, to me it’s really important to try to unearth and to make those connections to how we're living today,” she continues. This focus has only been sharpened by global events in recent months, Gwenessa says; particularly the pandemic and global protests against anti-Black racism following the killing of 46-year-old Black American man, George Floyd, by Derek Chauvin, a white police officer, in Minnesota in May.

Both events have shone a spotlight on the degree to which human lives are often lived in relation to looming, existential uncertainty, she adds. By way of illustrating her response as an artist, Gwenessa points to research she’s been conducting around an object in the collection of the Royal BC Museum and Archives in Victoria. This object, she notes, has yet to be conclusively identified. It’s also formally enigmatic, existing somewhere between a figurine and a vessel, or bowl, she says.

“The pandemic has made me really think about how we don't know what a body is," Gwenessa says. “And not only the pandemic, but in questioning racial and social injustice and who has rights to things, this little object suddenly has new meaning; because we’re unsure of its history, it has resonance today in terms of how we see. This uncertainty, to me, provides a really poignant parallel to a lot of what we're grappling with right now.”

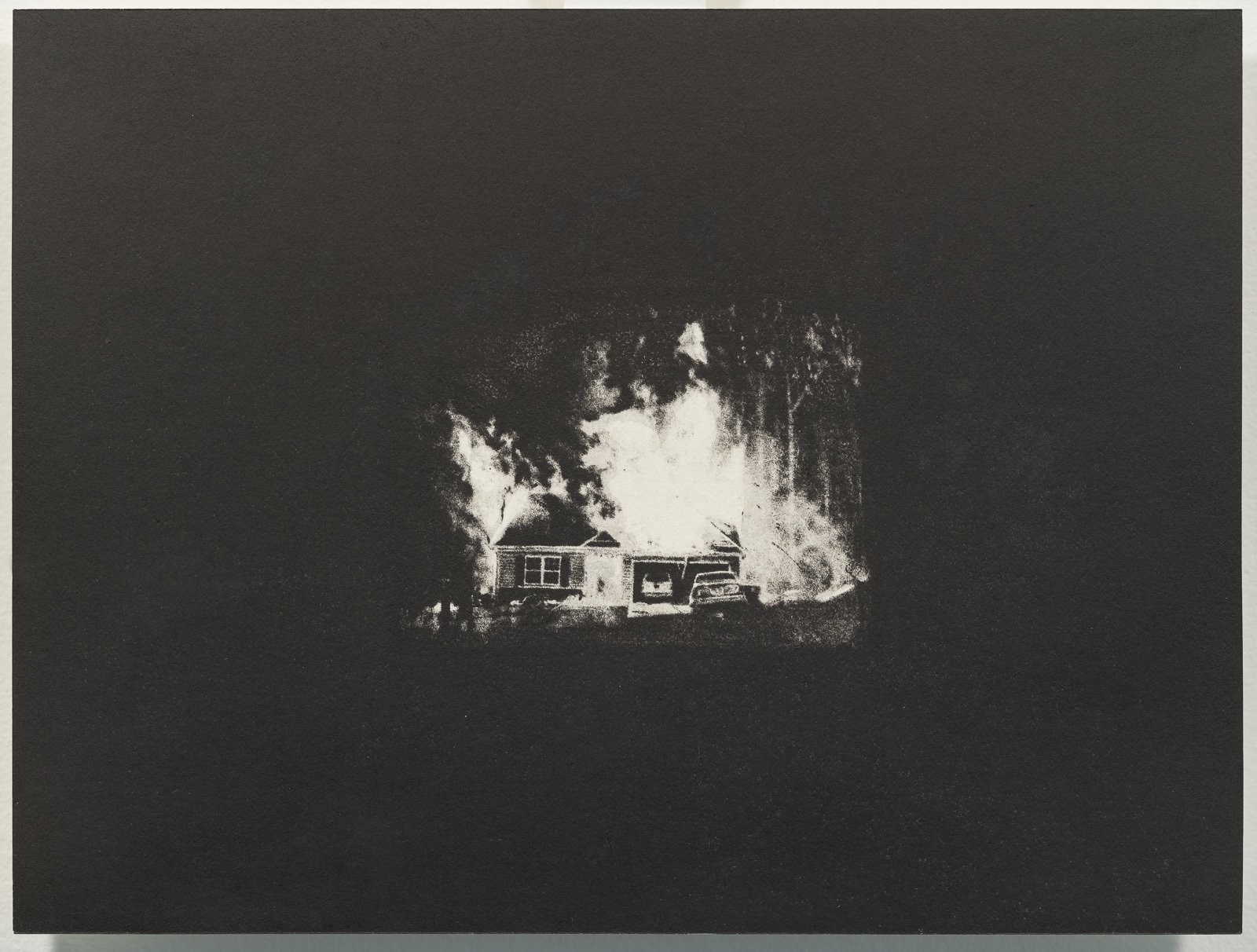

Gwenessa Lam, 'House (New Orleans),' 2012. Graphite on drywall.

In some respects, Gwenessa continues, the process of art-making itself likewise mirrors that grappling with uncertainty: an artist is constantly struggling to understand their subject matter; and the act of negotiating with a blank paper, canvas or wall is fundamentally one of being confronted with the unknown.

“When I'm making a painting or drawing — or, for my colleagues and friends who are writers or poets, that blank page, that blank screen — we are actually placed in relation to an absence,” she says. “You begin with an absence, and the process of making is trying to make whatever you want to communicate become present. That's an oversimplification of a more complicated experiment in the studio. But the studio is a space for that negotiation, of trying to communicate.”

Art-making is also a process by which intellectual, psychological or emotional realities are given a physical, sensorial form, she adds. In that sense, viewers of a work are not only encountering an object, image or experience, but are put into a position of negotiation with a sometimes-inscrutable other that requires work to be understood. The physical divide between viewer and work, she says, is likewise an “absence” that reflects the distance between individuals in the world outside the exhibition space.

“The viewer and the work are trying to bridge that physical gap through understanding, through a question of knowing: ‘I'm trying to understand what it is I'm seeing,’” she says. “I think art-making becomes a really interesting entry point to that relationship between presence and absence. And sharing that experience of negotiation with the viewer through the process of looking at a work is one of the things that motivates me to create.”