Meet Your (Critical) Maker

Posted on | Updated

Garnet Hertz and the Studio for Critical Making frustrate functionality to find the poetics which illuminate the impact of technology.

“Okay, Google: Who is Garnet Hertz?” Garnet calls into the depths of the room behind us.

“Garnet Hertz is a Canadian artist and academic,” 12 eerie digital voices reply. “He is known for his electronic artworks and for his research in the area of critical making.” The asynchronous chorus is both familiar and unnerving—like nothing you’ve ever heard before.

Experiments in Surveillance Capitalism is just one of the many interactive media projects Garnet is exploring at the Studio for Critical Making.

Experiments is scheduled to premiere this fall, in a public exhibition in the UK. But Garnet was generous enough to offer a special preview of the project, as well as the many others that are underway at the studio.

An object’s worth a thousand words

In his role as ECU’s Canada Research Chair in Design and Media Arts and Director of the Studio for Critical Making, Garnet uses a variety of techniques to help people engage more deeply with the tools and systems they use every day. Creating object-based works like Experiments, he says, is one of the most powerful ones.

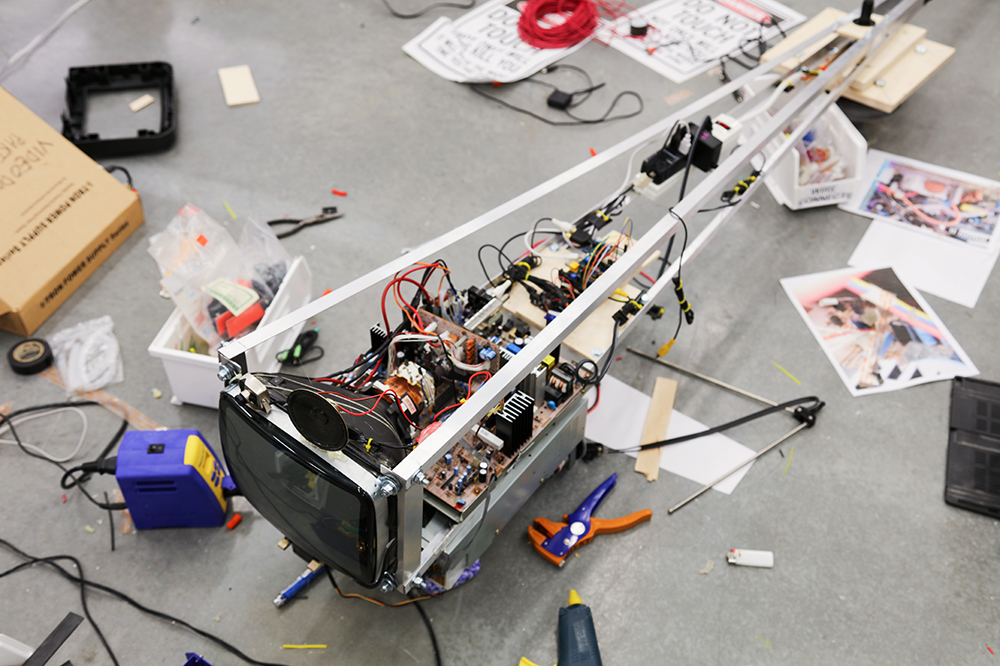

“An object is much more interesting for viewers … than a piece of software,” Garnet explains, gesturing to the complex contraption on the floor in front of us. “It slows things down and allows people to think.”

He continues: “As technology becomes more advanced, it becomes smaller, sleeker and easier to use.” But while this sleekness makes technology more user-friendly and efficient, it comes at a cost.

“It also becomes less legible,” he says, “you don’t really understand what’s going on.” Experiments aims to counteract this illegibility—to look beneath the smooth exterior of an emerging technology and examine the complex ethical questions that lie beneath it.

The projects stands amidst the many books, 3D printers and electronic gadgets strewn around the studio—a perfect circle of 12 Google Homes surrounding a bizarre, electromechanical arm. As we watch, the robotic arm crawls along the floor, moving from Google Home to Google Home like the hand of a giant clock. All the while, it “speaks” to Google, listing off terms like “ISIS,”“privacy” and “information terrorism” in a mechanical voice.

Each of these words, Garnet explains, is a search term reported to be tracked by Google and the US Government—a reminder of the privacy and surveillance concerns that now accompany almost every aspect of digital life.

The end result is both mesmerizing and unsettling—exactly as Garnet intended.

“Creating something that’s slightly strange, or slightly off centre, makes you feel uncomfortable,” he explains. That discomfort, in turn, can push you to consider the technology in a more critical way. To ask yourself: How do Facebook and Google build user profiles? What exactly do they do with your data?

“We tend to have a belief that everything new is automatically better,” Garnet explains. “But it’s always much more complicated with many unforeseen negative consequences … and I’m interested in highlighting that complexity.”

Subverting traditional production goals

Experiments is just one of the many design and art projects Garnet has spearheaded at the Studio for Critical Making. Since joining ECU as Associate Professor in 2015, he’s produced a diverse array of works, including a series of 3D-printed porcelain structures inspired by depressing global statistics, an alternative social media platform that connects users by fax machine messages, and an installation of life-sized origami figures who are just as obsessed with their smartphones as we are. He’s also exhibited his work in nine art exhibitions in eight countries, authored two books, and contributed to top-tier peer-reviewed computer science journals.

Although these research outputs may seem eclectic, they all share a common goal: to “increase—in a poetic way—the public’s thinking about the role of technology and the impact it has on people and culture.”

To fulfil this mission, the studio relies on a mix of innovative techniques that fall under the umbrella of “critical making”. This approach combines critical art practice with industrial design and academic research to produce creative, multidisciplinary projects with real impact. It draws on Garnet’s professional background in industrial, product and graphic design, while simultaneously questioning and subverting the established production norms in these industries.

“We use a lot of the techniques from product design,” Garnet says. “But instead of using them to create a better toothbrush or table, we use them in a more poetic or artistic way.”

Unlike traditional engineering practices that strive to maximize a product’s functionality, many of the studio’s outputs are intentionally counter-functional. The fax-based social media platform is one obvious example. Others include “Slow Game,” a comically unhurried “physical” video game inspired by chess, and Phone Safe, a lock box that prevents users from accessing their mobile phones for extended periods of time.

“Efficiency, speed and usability are all really good things,” Garnet offers. “But there’s always a tradeoff; it’s always efficiency at the expense of something else.”

By challenging these traditional production goals, the studio’s work “create dialogue and raise questions—they generate a more complex, human-oriented conversation” around these technologies.

Engaging the public through provocative publishing

But the studio’s focus extends beyond the world of object design. Books, zines, scholarly articles and other publications also feature heavily in Garnet’s work.

Although these projects look quite different from his other research initiatives, they examine similar issues. “I write about work that engages with topics related to ethics and social norms,” Garnet says, “work that challenges and questions.”

Take his most recent publication, Disobedient Electronics: Protest, for example. The limited edition publishing project highlights confrontational work by electronic artists, hackers, makers and industrial designers from across the globe.

“I wanted to explore using design objects to create dialogue around social norms,” he says, “to question the way things are done.” From an alarm clock that questions the gender wage gap to a “knitted radio” inspired by Istanbul’s Taksim Square protests, each of the unique creations in the volume is provocative or critical—a testament to how design can inspire social change.

Since its launch in 2016, Disobedient Electronics has been presented at some of the world’s most prestigious art institutions, including the Victoria & Albert Museum, the Pompidou Centre, and the Winchester School of Art.

But Disobedient Electronics is only one of many groundbreaking publishing projects. Garnet’s next major venture is to complete his book, tentatively titled Beyond Making: Do-It-Yourself Practices in Electronic Art.

"Artists, independent designers and makers often forge into unexplored technological territories, even with a lack of resources or professional expertise."

Currently under contract to be published with MIT Press, the book promises to make a splash when it’s finally released. Not only will Beyond Making be one of the first full-length academic monographs dedicated to exploring DIY electronics in art, it will also be the first to critically reflect on the growing field of the “maker movement” from an art history perspective.

Like so much of Garnet’s work, the project aims to illuminate aspects of the art, design and technology world that have been largely overlooked by the mainstream discourse.

“I’m highlighting many female artists and designers who have been working in this field about whom there’s virtually no writing,” he says. “Canadian artists and others who have been working in the media arts, critical design, and experimental music having doing this work for almost a hundred years: it is a fascinating field.”

Beyond Making is shaping up quickly, and Garnet is excited to see where the project will take him. He hopes it will offer a fresh perspective on how technology, design and the arts interact, as well as how creative individuals with a do-it-yourself approach can influence technological development.

“Artists, independent designers and makers often forge into unexplored technological territories, even with a lack of resources or professional expertise,” he says. “Understanding their work is key to understanding technological innovation—and to designing a better and more interesting tomorrow.”